How do artists sustain a creative life? Some focus on professional and artistic development, trusting that the merit of their work will earn them grants, commissions, patrons, or buyers. Some find (or marry someone with) a steady day job that allows them to separate their creative work from financial demands. Increasingly, some are blurring the boundaries between Art-with-a-capital-A and commerce, tech, and other sectors, often embracing the professional title “creative” over “artist.”1

Which tactics are sustainable, as we age, have a family or buy a home, or as the market changes? Does how we organize our creative work-life support the culture at large, or just stave off collections from month to month? What about our emotional health? What about creative growth? How do we set up our lives so that we have the energy to devote to our practice, and the resources to experience the world that informs it? This collection of problems have become an obsession of mine, as I work to reconcile my professional schizophrenia; to live a meaningful life as an artist, community member, friend, and role model for my niece; to navigate student and credit card debt, health care, and a broken academic system; and to plan for my future. I believe in the artist as a cultural catalyst, innovator, critic, chronicler, and healer, so, as hard as it can be, I refuse to give up my choice of career. I want to help cultivate a healthy ecology for socially engaged artistic practice, both as a practitioner and in support of my community.

In this essay, I’ll share with you some things I’ve done in the past couple of years in an effort to better provide for myself, and deepen my connection with an expanded network of peers, with the goal of growing a sustainable, “rhizomatic” community of artists and creatives. I’m drawing upon my knowledge and practice as a performance artist to do this; like my creative work, this is an experiment that I am approaching intuitively, from a place of curiosity. My approach is one among many, as artists and community organizers, globally, work to come up with better ways to live in an increasingly challenging socioeconomic and cultural climate. Perhaps my story connects with yours, and can be of use in your efforts.

I am a Los Angeles-based interdisciplinary performance artist and, recently, founder of a one-person company called Rhizomatic Arts, an artistic and social enterprise committed to connecting and empowering creative professionals for a more just, equitable, and sustainable culture. In the past twelve years, I've supported my own artistic practice as a full-time employee, part-time worker, doer of random “gigs,” and now I am mostly an independent consultant. I have an eclectic resumé of jobs working with artists, students, community centers, theatre companies, interior design firms, a Hollywood marketing agency, a San Francisco venture capitalist, and a women's studies center at UCLA. I’ve been office manager, production manager, bookkeeper, sales associate, and held a dozen other titles, but ultimately the “day job” strategy has never worked for me. I need a platform to develop my own projects, while growing my skills and helping others, on the kind of flexible schedule that works for my life. Now, as Rhizomatic Arts, I use my skills to support creative practice for a greater social good by providing professional services and training, organizing a peer network to exchange skills and resources, and initiating interdisciplinary art projects that explore different approaches to collaboration and interactivity. I don't think of my professional work as separate from my work as an artist; it is simply another way in which I am contributing to creating the world that I want to live in.

In botany, a rhizome is a horizontal underground root system that enables many plants to survive even an unfavorable season. The hearty root system supports multiple offshoots of blooms, stems and leaves above the surface of the earth. Ginger root is a rhizome, as are grasses and some flowers, like irises. In social activism, rhizomatic describes strong, horizontal structures: alliance that supports resilience and diversity. (We might be more familiar with the term “grass roots”—it’s the same idea.) In A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari contrast the horizontal rhizome that grows outward from the middle, with the vertical, hierarchical tree: “A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo. The tree is filiation, but the rhizome is alliance, uniquely alliance” (27).2 I believe that exchange and partnership on a person-to-person level produce a strong, sustainable community, with each of us personally invested in the success of our peers. My mission with Rhizomatic Arts is to counter paradigms of scarcity and competition with a culture of abundance, connection, and interconnected growth. The company’s credo is “Work independently, not alone.”

When I started working in 2010 on what I called the “Artist Sustainability Project,” I was interested in how ecology and “green businesses” might contribute to a professional model for artists. If a green business aims to “reverse environmental and social degradation” (to quote environmental entrepreneur Paul Hawken), we might think of a green arts business practice as one that aims to reverse the degradation of arts in education and civic life.3 It might aim to promote the sustainability of art professionals, validating the career path as a real, viable option for young people who are daily told art is "just a hobby" or "not a real career." In an ecology of sustainability, we would focus not on “getting the big break” or “being discovered” (which is passive and disempowering, as it implies that we are not in control of our lives and livelihoods), but on active collaboration and career building. “Growth” in this paradigm might not necessarily refer to the size of our budget or the number of tickets sold, but to stability, innovation, and impact on our communities.

Collaboration and exchange have always been central to my artistic practice. In school I was an organizer of clubs and shows. In college I founded an interdisciplinary theater company, working with poets, musicians, puppeteers, as well as actors and dancers. After graduation I benefitted from a decade of mentorship under Mexican performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña (my performance art padrino), whose company La Pocha Nostra has been globally influential in developing and sharing methods of trans-disciplinary “border-crossing,” rooted in the perspective of LGBTQI people and people of color. My performance work now mostly deals with social justice and moral action, with a focus on intimacy and collaboration. I produce critically charged encounters between performer and viewer that prompt each to consider the possibility for intimate exchange and critical solidarity. My one-on-one works suggest the possibility for intimate exchange within a formal art context. Participatory works such as "Witness" (a performance for one viewer-participant at a time) and "Your Photo-Op with Abby Ghraib" (in which I pose with audience members for torture themed tourist photos) invite viewers to insert themselves into the event and make ethical decisions about how to act. "Sibling Rivers", a site-responsive intermedia project, engages the social histories embedded in the rivers running through different cities, via a process of creative exchange across national and cultural borders. "Echo" weaves the stories of Echo Park, Los Angeles, with my own memories and family history. Now, under Rhizomatic Studio, the creative laboratory of Rhizomatic Arts, I facilitate workshops including the Collective Creation Lab (where makers of different backgrounds exchange strategies and practices for generating performance material) and Remote Collaboration (exploring co-authorship across distance and discipline).

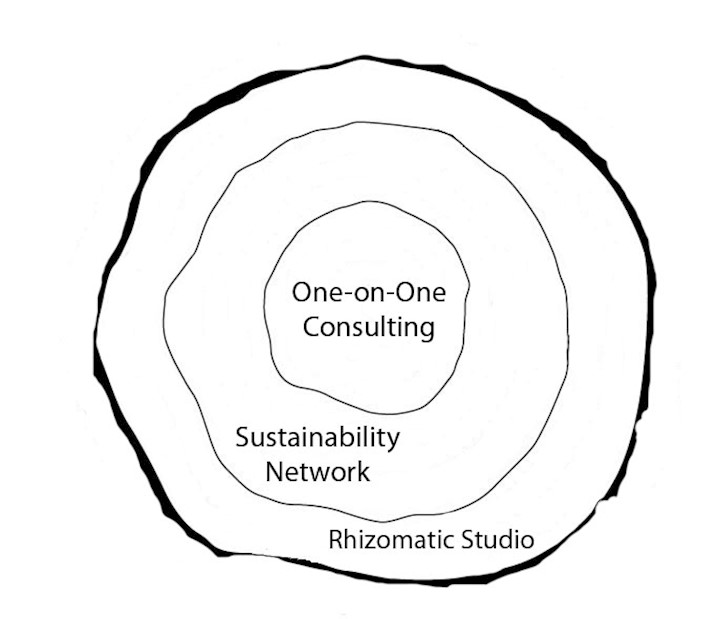

Rhizomatic Arts is my attempt to reconcile all of my disparate practices—performances, teaching, consulting, and design—into one, coherent entity. Articulating the structure and vision of the company was a bit of a process, and, in true Rhizomatic Arts fashion, I relied on a friend to help me talk through all of my ideas. We recognized immediately that Rhizomatic Arts would be a values-based practice—that central to everything we do would be the mission of cultivating community and sustainable practices. We started making lists: what are some things I want to do and things I don’t want to do with this endeavor? What are the values that are underpinning my different practices and what do those have in common? What emerged is a model that I think of concentrically, like the rings of a tree (see fig. 1):

Figure 1: Rhizomatic Diagram

- The core of Rhizomatic Arts is my one-on-one consulting work with individual clients (which bears some formal similarities to my one-on-one performance work, in that it is about establishing meaningful relationships with people).

- The next ring outward is building a network of creatives and artists who have skills they want to exchange, or just want to get together for cocktails and meet one another. (This has become the Sustainability Network, which I will describe below). This network also becomes, for Rhizomatic Arts, a pool of potential collaborators with whom I can work on projects, develop my skills, and subcontract elements of projects I take on.

- The widest-reaching, outer circle is everything I’m doing that is public facing: performances, writing (like this essay), and workshops.

To give an idea of how the rhizome concept plays in artistic or professional contexts, I offer two case studies. The first is the Collective Creation Lab, a performance workshop that I facilitated in Spring 2015. The second is the Sustainability Network, our second-ring, community-building project.

CASE STUDY #1: COLLECTIVE CREATION LAB

THE IDEA: an interdisciplinary performance-based workshop in which participants take turns leading structures for generating new material and playing with old, new, or undeveloped ideas, in a safe, supportive, interdisciplinary cohort of peers.

- The goal is not to create "a piece,” or even show anything we make to the public. The Lab is a place to play around, try out ideas, experiment with ways of working that are totally outside your wheel house, make BAD WORK in a fun, safe private space, etc. Or it can be the start of a new project.

- Structures might be borrowed from dance composition, devised theater, or performance art––or be completely original––and will be led by different members of the group each week.

- Participants can come from any performance-based discipline, and should be curious about trying out other ways of working.

- Each participant will be invited to facilitate (or co-facilitate) a session, but that is not a requirement.

The Collective Creation Lab began as an idea that I proposed to the community council at Pieter, a performance and community space founded by James Kidd in Los Angeles. “Pieter Council” is a loose community of approximately 150 artists of different disciplines who frequently teach, rehearse, or show work at Pieter. I was missing my grad school days, where course assignments shook up my practice and challenged me to make work in new ways, to examine how I was working, and why. The pitch was this: I have different structures that I use to make work, that maybe I’ve presented in different workshops, as well as conceptual and practical ideas that I want to explore. I proposed that we adapted a class structure that my friend Alexandria Yalj had been using, called “Collective Movement.”4 The idea of that class was to create a platform for different performance-based artists to explore their practices in a class setting, without worrying about cost. Different teachers were invited to teach master classes over the course of the year, offering their different techniques, styles, and approaches—so any given week participants would experience a different approach to dance making.

Borrowing from that structure, I facilitated a six-week workshop at Pieter, from 6-9pm on Monday nights. Eight artists from Pieter Council (actors, choreographers, visual and performance artists, and a PhD student) committed to the Lab, and we split the studio cost evenly. Everyone was invited to lead one week of the workshop (six of us volunteered), and the other participants would give a small donation to the facilitator each week. We quickly created a tight cohort by providing a safe, respectful, and totally supportive environment to experiment in. We decided against opening the classes up to participants outside our cohort, so we kept a small, consistent group throughout the six weeks. My role in the Lab was to facilitate structurally: I handled organization and scheduling, and set up a private Facebook group for the participants to share reflections, ideas and links. The participating artists were: Ahrum Hong, Gustine Fudickar, Brian Getnick, Maya Gingery, Loren Fenton, Gwyneth Shanks, Justin Streichman, and myself.

Weekly sessions were structured consistently: a day or two in advance, the week’s facilitator sent around a provocation, or idea, for the next session. These ranged from experiments in over-authoring each other’s work by exchanging materials and concepts, to Eric Morris’ 1970s actor training method “The Instrumentals,” to exploring character, plot, and text. The session usually began with a guided warm-up, followed by a short discussion of the provocation of the week, and one or more exercises to experiment with that provocation. Usually we would generate some kind of short performance to share, with anywhere from five to thirty minutes to prepare. Then we would discuss: what was interesting or useful about this method of generating material? Could we envision using it in our practice? How might it fit in, or not, with what we’re doing in our individual work? Are there potential pitfalls or challenges inherent in the approach? Where is it coming from, in terms of the various lineages of performance practices? How does it compare to other approaches? Sometimes the conversations would spill over into the week, with online discussions on our Facebook page.

Our intention was not to create “a work” as “a collective”—instead, we wanted to explore collectively-generated ideas and experiences as potential sources for performance making, and to create a temporary, fertile space in which to experiment. I am facilitating a second Lab in October and November of 2015, with one or two small changes to the administrative structure, and am curious to see what a new cohort brings to the experience.

CASE STUDY #2: SUSTAINABILITY NETWORK

The Sustainability Network is an online/offline community that connects artists and creative professionals with skills and resources to share, to promote hiring from within the local creative community while fostering partnerships, collaborations, cross-hires, skill sharing, and exchange. In this way, not only will each of us have more money in our pocket, we can also be enriched through new relationships that strengthen our individual practices and professional capacities. Members are invited to sign up on Rhizomaticarts.com, list what they need (a website, production support, studio space, documentation, etc.) and what they have to offer, and indicate whether they are willing to barter. You can browse member profiles or search by resource. We also hold monthly informal gatherings in parks, galleries, and private homes, where we enjoy tasty cocktails and talk about issues related to sustainability, community-building, and alternative economies. These gatherings connect people across the diverse professional, geographic, and cultural borders that often keep us separate in the notoriously vast Los Angeles landscape.

Here are two examples of how members might utilize the Network:

Example A:

MARIA is a choreographer who needs help setting up a bookkeeping system that is easy to use and won’t cost her a lot of money. She has years of experience fundraising for her dance company. JOY works part-time as an office manager at a creative firm, and has taken classes on bookkeeping for small non-profits. She is also a muralist who wants to start a street-art program in her neighborhood, and needs help finding funding to get started.

Maria and Joy both sign up for the Sustainability Network. Maria enters among her RESOURCES that she has skills in grantwriting, and NEEDS bookkeeping. Joy lists bookkeeping as a RESOURCE, and marks grantwriting as a NEED. Maria browses the member list, finds Joy, and emails her. Maria and Joy make arrangements to meet and exchange services. They decide to barter an hour of Maria’s time for an hour of Joy’s. Things go well, and they end up becoming friends, and contacting one another about shows and opportunities. Maria periodically hires Joy to help her with financial data entry when she get’s stuck. Joy asks Maria to write a letter of reference for a grant. A couple of hours of skill exchange leads to a lasting professional alliance, and each artist’s business capacity increases with the skills they’ve acquired.

Example B:

Greg is frustrated because he keeps getting turned down for grants. He believes in the quality of his paintings, but he has a hard time talking about them. He signs up for the Sustainability Network, and lists grantwriting and professional development among his NEEDS. (In the process of signing up, he realizes that his studio space sits empty while he’s at work, and he could rent it out part time, so he lists studio space as a RESOURCE.) Greg meets Betty, a grantwriter, who agrees to give him feedback on his grant application in exchange for a few hours in his studio. While browsing the site, Greg decides to contact Rhizomatic Arts for additional support, where he makes an appointment for professional development coaching and signs up for a workshop on writing about his work.

The Network models creative sustainability in two ways. First, it supports an independent, hybrid creative entrepreneur model as a way for artists to put our training to use in multiple contexts, while diversifying potential income streams. Secondly, it facilitates alternative and non-monetary economies by inviting bartering and collaboration as possible terms for reciprocal exchange. Furthermore, by recognizing the diversity of skills that many of us have as assets valuable to the community at large, we collectively re-define what creative practice is. Just in the process of signing up for the network, participants assess the skills and resources they already have, providing clarity around their own value as professionals. We are empowered to recognize the full scope of our skills, and broaden our understanding of the fields in which those skills can be employed, beyond the gallery or theater, into advertising, publishing, or design.

Many artists have had to think creatively about equitable terms of compensation. In the first Sustainability Network gathering we brainstormed all of the different terms of exchange or collaborative relationship that we have used or encountered in our art practices that might be useful in growing an alternative, exchange-based economy for artists. People described everything from barter, to mentorship, internships, or exchange labor for co-authorship/ownership of an artwork. An unfortunate fact of our line of work is that a lot of people in the art world don’t compensate one another, or even think that is a necessary conversation to have. At its worst there is a musty old idea still kicking around that ART and MONEY (like ART and POLITICS) should not even be part of the same conversation—which belies a level of privilege that most people I know do not enjoy. Within the Sustainability Network, we embrace an abundance philosophy that declares that there are more than enough resources to go around and we should all be able to pay our bills.

Rhizomatic Arts is now less than a year old, and it has a ways to go before it becomes profitable, but what I’ve found is that the people who are gravitating to this project want to share their experience and resources with one another, just as artists want their work to be seen, whether we’re being paid for it or not. (And hopefully, we are being paid for it!) We are, overwhelmingly, a generous species. Whether you’re an artist or a solopreneur, chances are your biggest demon is self-doubt, and isolation and competition tend to feed self-doubt. It helps to have at least one person in your corner, fighting your demons with you, perhaps providing some therapeutic perspective, or even cheering you on. Nothing about this life choice is easy, but so much about it is deeply rewarding. We are a fierce tribe, the independent artists of the world, and I want to see us thrive in my lifetime.

Rhizomatic Arts was germinated in Los Angeles in 2014, on the fringes of a local arts culture that embraces interdisciplinarity, and an economic and professional climate that requires D.I.Y. ingenuity and collaboration. It also comes out of a city with a complex and turbulent social history and, consequently, a powerful tradition of social justice work that integrates art into activism (witness Watts Towers, etc.). And ultimately, Rhizomatic Arts comes from my personal experiences encountering these environments, combined with years of professional trial and error that led me to believe that the only way I’m going to survive is by building a community around myself, reaching out for help, and then giving back whenever I can. Your experiences will be different from mine, and so too will be the solutions you come up with. My invitation is to look at the skills, the knowledge, the expertise that you have now, and use them as a place to begin. As the great theater director Peter Sellars says, our job as artists is to imagine the world we want to live in, create that world, and then live in it. I look forward to witnessing the worlds you create.

1. See the excellent Otis Report on the Creative Economy for a description of how the arts fit into the creative engine of the City of Los Angeles. back to text

2. Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus. Translated by Brian Massumi. U of Minnesota Press, 1987. 27. back to text

3. “Business is the only mechanism on the planet today powerful enough to produce the changes necessary to reverse global environmental and social degradation.” Paul Hawken, Speech to the Commonwealth Club, 1992, San Francisco, California. Qtd in SustainabilityNext. back to text

4. See Alexandria Yalj’s website for information about Collective Movement: back to text