Abstract

Beginning with the question, “If our practices aren’t helping us to become better people, then why are we doing them?” this brief reflection acknowledges the transformative potential of performance. It considers the way one practice of performance gave me space to recognize my own culpability in the actions of the US government, to grieve those actions, and to respond with humanity as an artist and citizen.

Kneeling on the red plush carpet, I inched towards the glass wall in front of me. Peering down on the first floor of this Los Angeles mosque, I had an aerial view of the room full of men below me, including the imam. Although he felt far away, his question to the congregation struck me with precision and immediacy: If our practices aren’t helping us become better people, then why are we doing them? His words marked my experience so strongly, it was as if they were tangibly imprinted on my skin. For months afterwards, whenever I found myself swept into unconscious busyness and distraction, those words pulled me back into that mosque—and into that moment. Since childhood, I have recognized performance as a practice that helps me to become a better person. The states of consciousness and presence that performance simultaneously conjures and demands have allowed me to be the most receptive, the most patient, the most generous, and the most compassionate person I know how to be. After working for many years to transpose who I was onstage into my daily life, I now actively look to the practice of performance to help me continually grow as both an artist and a citizen.

Soon after that sermon, I left California to accept a job in Mississippi. Sitting in my apartment one September morning, I read the news headline: “US Confirms Drone Attack that Killed 30 Farmers1 .” Although my apartment is no less than 12,439 kilometers from Nangarhar province, those words seemed to mark my skin as well, as I realized this atrocity and all others like it were also in my hands. As a US citizen, I convince myself that by paying taxes I am helping to feed children who need access to a free lunch at school or that I am supporting efforts to grow our national forests. In truth, I know that much more of that money is used to manufacture and deploy weapons—and I share responsibility in that as well.

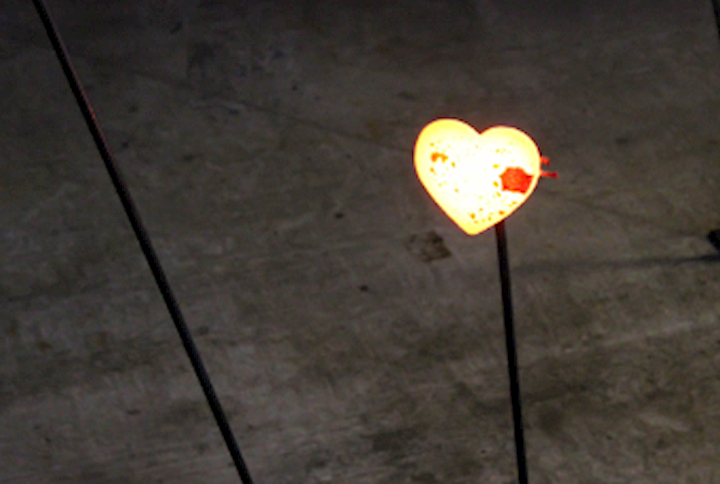

So, I looked to performance to help me understand how to take responsibility—how to offer a response that honors the humanity of those farmers. In collaboration with sculptor Kevin Vanek, I created a performance installation in remembrance of them. As we were planning the performance, Kevin had a vision of me dancing in a field of iron hearts, and suddenly I realized that those 30 hearts could acknowledge each of these Afghan civilians. Yet, throughout the process of creating the performance, I doubted that my actions could actually honor them. Why would dance be a way to respect their memory? Answering this question within myself revealed what I believe is possible through the practice of performance. At a time when many citizens in the United States and around the world seem to hate other people that they have never met, for some reason I have been given the gift of loving people I have never met (and I suspect many artists have that gift). It is that love that moves me to dance. Thus, the title of our performance references writing by Khalil Gibran in his famous book The Prophet: “Work is love made visible2 .” Performance can be love made visible.

Thirty hearts gradually accumulated in the plaza that night. As each new sculpture was formed, I moved in memory of those farmers that I had never met. “Jabeen was the only wage earner for his household—a wife, four children, and his elderly father. He made 400 Afghanis ($5) a day harvesting pine nuts3 .” Rising slowly, I unfurled my right arm. “Wahidullah had just married4 ." I rotated quietly between two hearts. “Abdullah was the father of two children5 ." Curving to the side, I descended again. “Ibrahim left behind a wife and three children6 .” The movement itself was a meditation on and for peace. Just as I have experienced performance as a vital state of consciousness for helping me to become a better person, I believe in performance’s transformative power as a meditative practice for societies as a whole. As the research data from the “International Peace Project in the Middle East” reveals, meditation by even 1% of a population positively correlates with a dramatic reduction in violence7 . Therefore, I invited the audience to join me in sending thoughts, prayers, and meditations for peace during this performance to our country and to the friends we know in Afghanistan as well as those we have never met.

Kneeling on the gritty concrete, I softened the tops of my feet into the raw surface and gradually opened my eyes. The ground was peppered with fragments of cast iron that we had broken into pieces and then melted into hearts. Peering down on me in the sunset lighting, a crowd of both friends and strangers held a silent vigil. I danced until all of the hearts lost their glow, and then respectfully slipped out of view while the sculptures continued to stand in remembrance.

1. “US Confirms Drone Attack that Killed 30 Farmers,” Al Jazeera, September 20, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/09/20/afghanistan-us-confirms-drone-attack-that-killed-30-farmers/. back to text

2. Khalil Gibran, The Prophet. (New York: Knopf, 1923). back to text

3. Kathy Gannon. “Anger grows at civilian deaths by US, Afghan forces,” PBS News Hour, October 6, 2019, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/anger-grows-at-civilian-deaths-by-us-afghan-forces. back to text

4. Gannon. back to text

5. Ibid. back to text

6. Ibid. back to text

7. David W. Orme-Johnson, Charles N. Alexander, John L. Davies, Howard M. Chandler, and Wallace E. Larimore. “International Peace Project in the Middle East: The Effects of the Maharishi Technology of the Unified Field,” The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 32.4 (1998), 776-812. back to text

Works Cited

Al Jazeera. “US Confirms Drone Attack that Killed 30 Farmers.” September 20, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/09/20/afghanistan-us-confirms-drone-attack-that-killed-30-farmers/.

Gannon, Kathy. “Anger grows at civilian deaths by US, Afghan forces,” PBS News Hour, October 6, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/anger-grows-at-civilian-deaths-by-us-afghan-forces.

Gibran, Khalil. The Prophet. New York: Knopf, 1923.

Orme-Johnson, David W., Charles N. Alexander, John L. Davies, Howard M. Chandler, and Wallace E. Larimore. “International Peace Project in the Middle East: The Effects of the Maharishi Technology of the Unified Field,” The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 32.4 (1998), 776-812.