Abstract:

This paper seeks to analyze metaphysical questions through the lens of my own artistic practice. It will seek to develop a system for understanding the first-person experience of a dancer and how meaning is translated through choreography. In a multimedia format including photo, video, performance, and analysis, it will demonstrate how art, more specifically dance can complicate the mind/body dualism that holds that the mind and body are separate substances comprising the whole of a human being. Using Friedrich Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy as inspiration, the dance piece itself, titled “Notes on Form,” seeks to synthesize his work with various metaphysical questions as the basis for the movement vocabulary and as a lived manifestation of various philosophical debates, such as mind/body dualism, epistemological questions regarding experience and reality, and existential questions surrounding the nature of our being1 .

As part of my process in creating a piece that experiments with the translation of meaning and embodiment, I asked the cast of my piece “Notes on Form” a series of questions about meaning, mind, and body and recorded their answers. I draw on these expressions of the dancers’ lived experience of dance throughout this article and present them anonymously to illustrate the power of dance to blur the line between mind and body, and to demonstrate the individuality of each dancer’s intimate relationship with movement, self, and others.

The Mind and the Body

“There’s a kind of connection between the mind and body that is so deep that I think it’s difficult to see it sometimes. They work together in a way that, to me, feels seamless and they almost ‘fill in the blanks’ for each other.”— “Notes on Form” Cast Member

Metaphysics is a specific branch of philosophy that is concerned with the nature of reality, existence, and the connection between the material and immaterial. It is seemingly about everything all at once, for it asks us how we can make sense of our experience. Metaphysics explores concepts that seemingly go beyond the scope of sense experience and empirical, physical science and rather deals with aspects of reality that cannot be easily observed, measured, or parsed down into some operational definition. These questions ask us to go beyond the mere fact that we are living and therefore exist in some way, in some space, at some time and asks ourselves what constitutes that existence? Are there fundamental substances or entities that exists as the common substratum of humanity? Or can it be reduced to something more basic, like simply an atom? How do things even come into existence in the first place, and can we discover, truly, what those causal connections are? What is the relationship between mind and matter? Are the mind and body separate entities, or are they one thing? And if they are separate, what is the nature of the interaction?

The nature of the interaction between our minds and our bodies is one of the many seemingly unanswerable questions we encounter in philosophy. I argue that dance can provide insight regarding the nature of the interaction between the mind and the body, posing yet another logic problem to the various responses to the common-sense view of interactionism, or the view that the mind and body are distinct substances that interact in some way, creating the informed whole of the human being. It seems that mind and body do not share the most basic intrinsic properties. For example, the body is made of flesh and bones: matter. It can be pared down to the smallest, most basic particle and we can understand the minutia that comprise the material body. The mind, however, is not seen as something material. We cannot touch it and we cannot necessarily derive its spatial location (under the premise that the mind is something that exceeds the thing we call a brain).

Our minds are our experience of thoughts, emotions, and the processing of stimuli; what makes us sentient beings. The common-sense view regarding this matter states that we are comprised of two entities, a mind and body, that each affect each other. However, this materialist view is far too reductive. We can perhaps see how pain travels through the central nervous system to the appropriate part of the brain, but that is not the full experience of pain, which also entails the weight of one’s inner experience as it pertains to what we feel when the body is acted upon. Similarly with pain, while true that feelings associated with love can be seen in various chemical reactions in the brain, love is also manifested through intentional action. As with love and pain which so bridge the mind body gap, dance likewise poses a problem to the materialist camp, for our states of mind are consistently reflected and honored within movement.

“My mind and body are directly tied together when I am dancing. How my mind is feeling will reflect on how my body is moving. It's a physical representation of the state of my mind. It is similar to my body. Based on the state of my body, it can change the state my mind is in.”— “Notes on Form” Cast Member

“I think a lot of the time my conscious mind is thinking about a lot of the specifics that maybe my body hasn’t turned into muscle memory yet. Sometimes my mind feels completely blank when I am moving through and it feels as though I’m “thinking” through my body.”— “Notes on Form” Cast Member

When I perform on a stage, it is the result of the intimate conversation unfolding through movement. What you see is the essence of my body and mind conversing. Rather than thinking this dance performance is “merely a brain function” or is “entirely physical,” audience members might wonder, “how is it possible to do all that? How do the dancers remember the steps? How did the choreographer construct this coordination of movement?” The answer goes back to the constant dialogue between the mind and the body and a deep understanding of how the two are profoundly connected in every instance. This takes practice to fine-tune. At times, there is an inability to translate thoughts or concepts onto one’s physical body. For example, when I am creating, it takes time to take the image in my head and turn it into movement. The inverse is true as well, sometimes I will be improvising and I feel myself do something interesting, but when I go to replicate it, the mechanics do not come as naturally as expected. Eventually, though, the gap is bridged. We become living, breathing byproducts of the physical and mental, and the dancer’s experience through artistic expression is the living-out of the intimate dialogue.

The One Responsible for Art: Nietzche's Birth of Tragedy

Art is the highest task and the true metaphysical activity of life— Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

Nietzsche believed that art and artistry help us transcend the bruteness of the world, giving permission for us to let the light in. “Without art, we would be nothing but foreground and live entirely in the spell of that perspective which makes what is closest at hand and most vulgar appear as it if were vast, and reality itself ” (Nietzsche 1887, 166). For us to have a deep understanding of life, Nietzsche argues that allowing ourselves to indulge both our Apollonian and Dionysian impulses provides catharsis from the chaos of existence.

The Apollonian impulses can be described by the nature of Apollo himself, the Greek God of everything that is light in this world: the sun, music, dance, truth, and healing. Dionysus is the Greek God of pleasure, wine, fertility, festivity, and ritual madness. He is described by Nietzsche as “the eternal and original artistic force” (Nietzsche 1910, 168). Through this Dionysian impulse, we can access “the very essence of the world, an insight that lies beyond the pale of science and scholarship. The remotest regions of life reveal themselves only to the ecstatic vision of the Dionysian artist, whose highest type is represented by the musician” (Bluhm 1942, 24). The union of these two artistic forces, one being the rational representation of beauty and form, and the other representing the primal, chaotic, and ecstatic, is exhibited in the stories of Greek tragedy, but also in life. We are asked not to suppress these impulses for the mere appearance of harmony that is described by Apollonian impulses, but rather give in to our intrinsic duality, allowing us to embrace the fullness of our spirt.

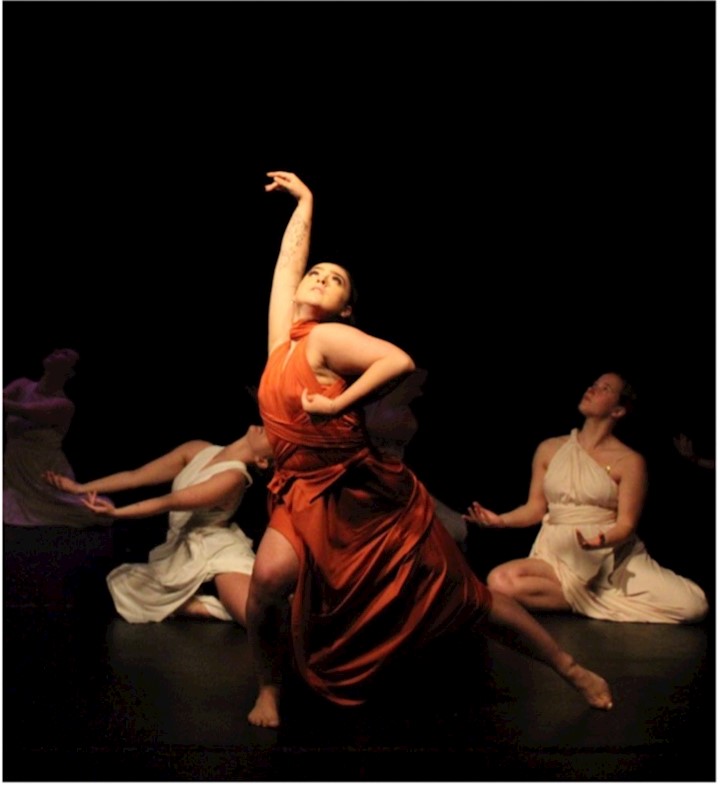

The Dionysiac Impulse; Photo: M. Hemenway | Dancer: Jessica Taddeo

Nietzsche believed that all humans stemmed from something common, “the Primordial One.” This is not necessarily the figurehead of God, or a specific religion’s conception of God, but rather an underlying commonality, perhaps the Apollonian and Dionysiac duality. Furthermore, he believes that dreams regarding higher ideals such as goodness, holiness, virtue, wisdom, and beauty are made manifest in art, music, poetry and tapping into primal instincts and movement. Therefore, art exists as a representation of all that is good and holy: the mystical, the metaphysical, spiritual part of the world. The order of the universe, and humanity at large, bends towards fostering this expression. If all humans are profoundly connected through the duality, with the universe and with each other, art, expression, and more specifically dance is truly magical and Godlike. The expression brings us the closest we can get, as mortal beings, to what brought us here, and towards an understanding of the metaphysical.

Coming Into Being: The Origin

Everything comes into being. Everything has an origin, everything has a purpose, everything has a composition, and everything has an end. – Lecture Notes, Metaphysics, Spring 2023

Over the course of my life as a dancer, I have watched myself correct my hyperextended elbows, my arched lower back, and my pinched shoulder blades. I have learned to relax into my femoral fold, and I have learned to trust my own strength. My authentic movement practice (improvisation) has morphed from doing as many impressive things as I can in a short amount of time just because I am good at them, to learning the importance of stillness, breath, space, connectivity, and shape before all else. Through a lifetime of adjustments and learning, I can still find movement that is quintessentially my own. When I received a higher education in dance, I learned how to work with my body, as opposed to having my body work for me. I learned the importance of fostering a symbiotic relationship between mind and body that was not dependent on any one person’s idea of what dance is supposed to mean. When I was younger, I treated my form as something that was purely responsive or performative. I would be given choreography, and I would think two things: how do I do this, and how do I make it look pretty? Dance was for the stage before it was about anything else. We aimed to please, and to be perfect, for both an audience and us. This is not to say that it could not be expressive or emotional, but it is to say that those expressions at times were more artificial than authentic.

I have found videos years apart of authentic movement that, in essence, were the same. I had no memory of either instance, neither day stuck out to me in particular. However, when I stumbled upon this happy accident, it struck me as profound. An identity is sustained despite the seasons of life passing by. As an artist, this is something to hold on to. As a philosopher, it is something to call into question. It is an instinct, resting on some core, unchanging part of the self, that allows that manifestation of the self to develop. In my case, this is demonstrated through dance. The same is true for a painter, sculptor, photographer, and even poet. The work reflects the artist in all of her multitudes.

My choreographic process in the dance piece inspired by Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy is a mix of concrete ideas, spontaneous creations, and “staffing it out” to the cast. At its core, dance is an expressive art form that is contingent upon identity, body, culture, and movement. Thus, honoring the individual artistry of all eleven members of my cast was fundamental to the final form of the piece I named “Notes on Form,” because in essence, it is a demonstration of how we are connected to things and by things that we cannot always see or touch, but rather feel.

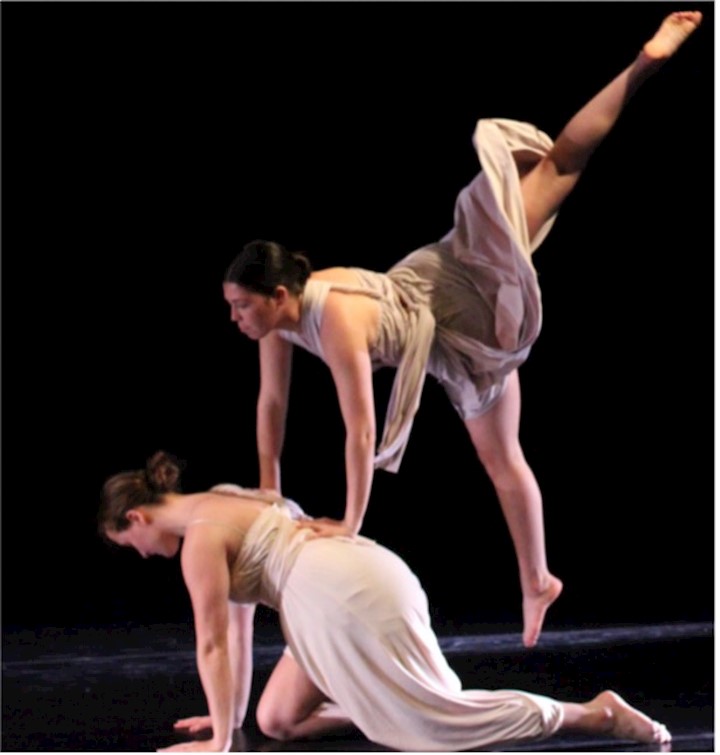

Photo: M. Hemenway | Dancers: Gabriella Poulin, Emma Trahan

Coming Into Being: The Composition

There were two things I knew for certain when I began the process of creating “Notes on Form.” I knew the primary music score would be “Space Song,” and I knew that I wanted to emulate Raphael’s “The School of Athens.” In the center of Raphael’s fresco, Plato is seen on the left pointing to the sky, and Aristotle is seen on the right gesturing towards the ground. They are surrounded by some of their contemporaries, including Socrates, Xenophon, and Heraclitus. The two are gesturing in their respective directions to indicate what is “real” – the material, sensed world, or the immaterial world. Not only did I want to invoke this iconic image, but I also wanted to hold this duality in tension. As for a cast, I knew I wanted a large group to demonstrate the one and the many, meaning I wanted to demonstrate the connectivity of all humankind, but also to demonstrate how we are the makers of our own truths via our own choices.

“Notes on Form” is a story told in three acts. In the first, Nietzsche’s own words in English translation set the scene. In Act II, a cello cover of “Space Song” represents the delicate, classical, Apollonian quality. Most of the dancers are joined together in unison, eventually breaking off into smaller duets and quads demonstrating the contrasting movement styles. Finally, in Act III, original version of “Space Song” represents the descent into Dionysiac impulses, which are further evoked by the incorporation of more dynamic movement. I sought a cast that was similarly interested in the conceptual aspects of art, dance, and performance. The dancers expressed to me that they felt comfortable in the piece, they felt beautiful in the piece, and most importantly, they felt themselves in the piece.

I started rehearsals with “task-oriented” prompts; a compositional tool often used in dance. Give a task, based on concepts, and allow the dancers to create a phrase based on the instruction. Contrast is one of my most influential choreographic devices in my own process, so I began from what I knew. Taking a page from William James, I had the dancers classify themselves as either tender-minded or tough-minded. The tender-minded individual is more rationalistic and driven by principles. Idealistic, optimistic, spiritual, and free-willed, the tender-minded individual is more likely to wander into the realm of the Platonic forms for explanations of reality. In contrast, the tough-minded individuals are driven first and foremost by facts and practicality. They are the more grounded of the two, leaning on more material, agnostic, fatalistic, and skeptical visions of the world. Then, they would work within their classifications to create a phrase rooted in their embodiment of these concepts. Some of the dancers felt torn between the two, which prompted me to create a third category, one they named the “tortured-minded.” We created different movement qualities to represent and embody the three classifications. This would become Act II of the piece.

Tough, Tender, Tortured, 2/6/23

The tough and tortured dancers created one phrase, and the tender-minded created another. When they were finished creating, I asked them to perform the two pieces at the same time. The tortured-minded dancers abstracted parts of the phrase to demonstrate the movement quality of both camps. This was the most important concept driving the dance forward and it became the seed followed throughout.

The role of Dionysus is a central figure in “Notes on Form” and is meant to embody the truly primal impulse. As such, dancing the role myself, I had no specific choreography. The authentic human impulse, the divine order birthed from chaos, is honored in my movement. The rich orange fabric of my dress contrasted with the godly whites and neutrals of the cast to demonstrate the darker Dionysian impulse. In addition, I wore my hair down in contrast with the sleek ballerina buns donned by the cast and let the back of my dress hang open to tap into Dionysiac sensuality.

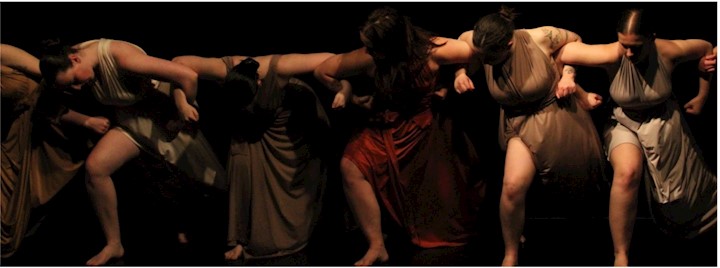

Photo: M. Hemenway | Dancers from left to right: Davis, Grady, Huntington, Taddeo, Trahan, Menendez

Solar Plexus Stomps, Tender-minded phrase | Photo: M Hemenway

In addition to a tableau of the School of Athens, another image that struck me and that I wanted to weave through “Notes on Form” was a strong line with all of the dancers side by side in a gradient of neutral colors. In addition to the Dionysian and Apollonian Duality, as well as the tough, tender, and tortured relationship, I worked with the idea of coming together and breaking apart. I wanted it to look like breathing and unfolding. Horizontal lines and a center-stage cluster would become the places of coming together before breaking apart to honor individual experiences as the story continues. From the initial horizontal line, the “many” began to break off.

Tough and Tender Duet I, Photo: M. Hemenway | Dancers: Gabriella Poulin and Zoie Vail

Each duet had one person from each movement style, the trio having a tough, tender, and tortured. If the dancers were not in the pair being performed, they maintained various unison movements. The “coming and going,” or to honor the lyrics, “falling back into place,” was both my choreography as well as the original tough-minded phrase that I had changed slightly. The duets come in and out, as the remaining dancers in the Chorus travel in a group across the stage, ultimately taking two formations before breaking into a circle with the trio entering through the back and into the center. The circle completes a small floor phrase to contrast the height of the lift occurring in the center. The dancers break away from the circle as the trio culminates with a lift, and the transition to Act III begins. The dancers “fall back into place” with a simple walking pattern, first by creating three horizontal lines, moving into one, and separating into two as the music and lights change. We are reminded of the Dionysiac impulse again as the lights create orange and pink shadows, the cello changing to synth as the original “Space Song” rings out. This was the final descent into the orgiastic, dynamic impulses that have underscored the entirety of the piece. It was time for each of the dancers to abandon their neat classifications and to embrace the connection with all of their multitudes. This final phrase was created by the cast, which tasked them with demonstrating how they have each internalized the movement vocabulary. After this group phrase, the dancers come together one final time in a circle in the center, breathing to the left as they look inward and breathing to the right as they look outward, their arms going up in contagion before breaking away to a set of lines for the sauté arabesque section. This was one final nod to the classical, linear movement vocabulary intrinsic to Act I and Act II. The dance ends similarly to the way it began, with arms shooting up to the heavens and retrograding back down to the palm-up formation of the Greek statues. To create the final image, stillness is found within all of the dancers except one, who is the only one moving as the lights fade from the shadowy white from the beginning, and then finally, to black.

Coming Into Being: The Purpose

“You always have a feeling that you are more than human.” – Pina Bausch, dancer & choreographer

I’m very interested in being a medium for art, as well as being an artist all in the same vessel. Dancers have the ability to represent symbolism, and also exist as people on stage depending on the choreographer’s intent. For me, this means transcendence of the physical form, but also being incredibly connected to my physical body.— "Notes on Form" Cast Member

“Notes on Form” sought to encompass many things, including translation of meaning among the choreographer, dancers, and audience and how that complicates appearances and the supposed reality. Whatever impression is conjured up is the viewer’s truth, but it is not the only truth. When I am on stage, I try to remember all of the things I am meant to embody in a piece. Oftentimes the choreographer will tell you what you need to portray, but other times it is up to you as a dancer to manifest the choreographer’s vision. When giving movement quality prompts to them one day, regarding the positioning of the hands and arms and space, I said, “you are to become like stardust. You are amongst the Gods in this dance. You are to feel as though you can take flight at any time, but between those moments you are rooted, strong, and here. As you move through space, feel as though the universe is in the palm of your hand. Where is that bringing you? Where can it bring you? What does it mean to be connected to something that profound?”

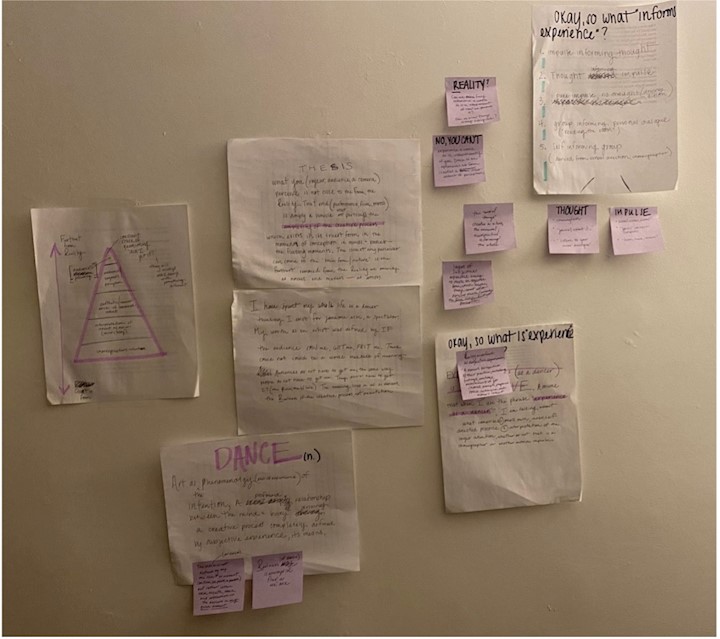

The Original Mapping of The Creative Process: Notes on Form, October 2022

What the audience or the camera perceives is not close to an objective understanding of reality. That end, which is the performance, photos, or film, is simply a vehicle that portrays the appearance of the complexity of the creative process. Reality, as opposed to mere appearance, exists in its truest form in the moments of conception, both in minds and bodies. Reality exists in the rehearsal spaces and in the mismatched pen scribbles in notebooks. It exists in the trial and error of phrase work, timing, and composition. It exists in the moment where each dancer pictures the root of the universe extending from their limbs. When witnessing these fleeting moments as the piece comes alive on stage, the closest the audience can come to the truest nature of the piece is, in actuality, the furthest removed. The product is the manufactured, Apollonian appearance, but the process is the primal, human, Dionysiac essence.

Coming Into Being: The End

Dance, especially modern, would not be possible without a mind body connection. These are our two main motors of our souls. As dancers we are able to have these things connect and fully work together, and our soul produces something beautiful, art. If we just used our body or just used our mind, the movement would look incomplete, the meaning would disappear, and the true art would be lost.— "Notes on Form" Cast Member

This thesis existed to defend dance as an uncongenial remedy to core questions of philosophy, but it was also an extension of myself. I was creating for the sake of doing what I love, yes, but I was placing a wholly personal process into a formula from which I can deduce something. In addition, I was introducing a group of people to concepts that were not only heady but foreign. I had a delicate balance to strike between movement and philosophy, and I could not compromise the integrity of either in the process. When I stepped into my professor’s sunlit office to workshop the analysis portion of the paper, it was about making sense of the foundation. What am I aiming to prove? What did I need to understand to turn a widely accepted perspective on its head? Was there something to be said here at all? When I stepped into the studio, it was about embodying that foundation. How were the words of Nietzsche literally coming to life? How were the hypotheses of those I have read in class becoming complicated by my lived experience as an artist? As dancers, and by extension, people, how are we maintaining a collective consciousness and identity, but also being true to ourselves in a way where we can stand alone?

Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy is concerned with what the philosopher considered the highest form of art, the Greek tragedy, because it blended the Apollonian and Dionysian elements together, allowing the audience to take in a full expression of the human condition. In “Notes on Form,” I take inspiration in the tragedy’s ability to encompass the human condition and through the process of creating the piece, I came to appreciate dance as a form of human expression that can throw into question the mind/body dualism of the materialist philosophers – an idea that continues to inform a grammar, at least in English, in the ways we can understand ourselves. Dance allows us to free ourselves from spoken language alone and blend the more primal aspects of our human condition and thereby transcend mind/body dualism.

Act III, Retrograde, Photo: M. Hemenway

1. This paper initially existed as my graduate requirement for my Philosophy degree, completed in collaboration with Dance and Philosophy faculty at Roger Williams University. This publication is abstracted from the full thesis, titled “The Creative Process Notes on Form – A Study of the Metaphysical Underpinnings of Movement” which was awarded thesis with distinction upon my graduation in May of 2023. back to text

Works Cited

Bluhm, Heinz. 1942. "Some Aspects of Nietzsche's Earlier Conception of Art and the Artist." Monatshefte für Deutschen Unterricht 34 (1): 23-27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30169845.

Broad, C.D. 1925. "The Traditional Problem of the Mind and Body." In The Mind and its Place in Nature. London: Routledge.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1872. The Birth of Tragedy & The Geneaology of Morals. Translated by Francis Golffing. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company.

---.1887. The Gay Science. Leipzig: E. W. Fritzsch.

---. 1910. The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche. Edited by Oscar Levy. 18 vols. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: T.N. Foulis.