Introduction

On the evening of the second Saturday of every month, around 8:00 pm, I, with a few close friends, ascend the steep flights of stairs to the third floor of Vox Populi, a space run by a collective of Philadelphia based artists that was founded in 1988.1 The gallery is small and industrial, with a few rooms dedicated to fine art and media exhibitions contributed by the members of the collective. We are not at Vox (as I often hear it abbreviated) to see these exhibitions, however. Instead, we are asked to donate a few dollars by a young woman at a podium before entering through a set of curtains into the black box space, a room designed for special musical or theatrical performances. The room is small, only 20 feet by 45 feet, and every surface, including the small stage at the opposite end of the room, is painted matte black. Up above, a simple grid of theater lights shines colors of green, blue, and red onto the stage, where large speakers have been arranged to blast sound into the audience.

An emcee, one of the coordinators for the monthly gathering, gives a welcome to the audience; she calls the event “8Static”. Most of us in the audience know her, so she makes a few raunchy jokes and everyone laughs. A camera man films the event from the back of the room, which he uploads into a “live feed” for people elsewhere to watch in real time on their computers. A woman sells T-shirts and stickers at a merchandise table. The emcee introduces the first musical artist of the night. A boyish looking man steps onto the stage and plugs in his instrument, an old Nintendo Gameboy. A familiar ping ping of the machine gets the audience excited. He begins to play his song. Everyone, including the performer, begins to dance.

This is “Chiptune”.

A visual artist well known in the Philadelphia “scene” recently introduced me to Chiptune. Here, I understand the use of the word “scene” within Chiptune communities as a designator of “the contexts in which clusters of producers, musicians, and fans collectively share their common tastes and collectively distinguish themselves from others”, according to the definition given in Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual.2 Prior to attending my first Philadelphia show in January 2016, I had no knowledge of what Chiptune was. Furthermore, my knowledge of musical subcultures was very limited. I have, however, cultivated an extensive body of knowledge regarding dance theory and practices. A lifelong mover, I grew up taking ballet and jazz classes through a studio in my almost exclusively white community in Michigan. Being white, and a female, I was part of the rather obvious hegemonic group within my studio setting. I had similar experiences during my undergraduate studies at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. Not until beginning a Master’s of Fine Arts program at Temple University did my current research interests begin to develop.

In particular, my scholarly research focuses on social dance and movement improvisation as they relate to community and belonging. I am also interested in Sally Ann Ness’s monumental work with inscription and gesture, and how we might apply her theories to dance forms other than “classical” forms, which Ness defines as forms that are “tradition-bound, technically developed, and hierarchically institutionalized3 ”. How then has my research in dance influenced my interest in Chiptune music? To understand this, one must understand that the Chiptune musical movement is not solely a musical entity. In actuality, the scene is a triangular amalgamation of music, visual creations, and physical movement. Furthermore, Chiptune is rather unique in that its participants are generally from the same generation, known as generation Y, or the Millennials, of which I am a part. These are the young adults of today that would have had access to early 80’s and 90’s gaming technology.

After attending many live shows in Philadelphia, and a few in New York and Washington DC, I began to notice a few unique traits pertaining to how the body was used, and discussed, within Chiptune. Certain aesthetics are apparent: bodies pack towards the stage as the show begins. Many people wear their favorite artist’s T-shirts or buttons that are sold at every show. Bodies of all shapes and sizes comprise the crowd, most of them white but a few are African American, even fewer are Asian American. An overwhelming number of them are cisgender men; the women in the audience are there usually as a partner to one of the artists or are brought there by their male friends. Women, however, are not absent all together. The head organizer of the Philadelphia monthly event is a woman, and many “big name” Chiptune artists are in fact cisgender women. Most of the folks have day jobs, some in music, a majority not. There are a few in the crowd who are part of the transgender community. What I see, in fact, feels like a fairly diverse crowd. These diverse backgrounds and identities do manifest themselves in the audiences’ movement choices, but I am not suggesting that a certain body moves a certain way because it is black or white. Rather, I suggest that the way chip enthusiasts move and handle their bodies might be a sign of group values within the Chiptune music scene that can be witnessed through movement of the body and of the collective group. My main argument in this essay is that the values of Chiptune are made visible in the body movements seen at a Chiptune show. While I have identified many values associated within Chiptune, I will focus my research on two: individualism, and investment. I will be evaluating the movement aspect of live Chiptune shows and identifying key elements of the rather unique use of movement, to figure out what they might suggest about the larger values of Chiptune, and other subculture music movements and the sense of belonging that comes from them.

Chip History

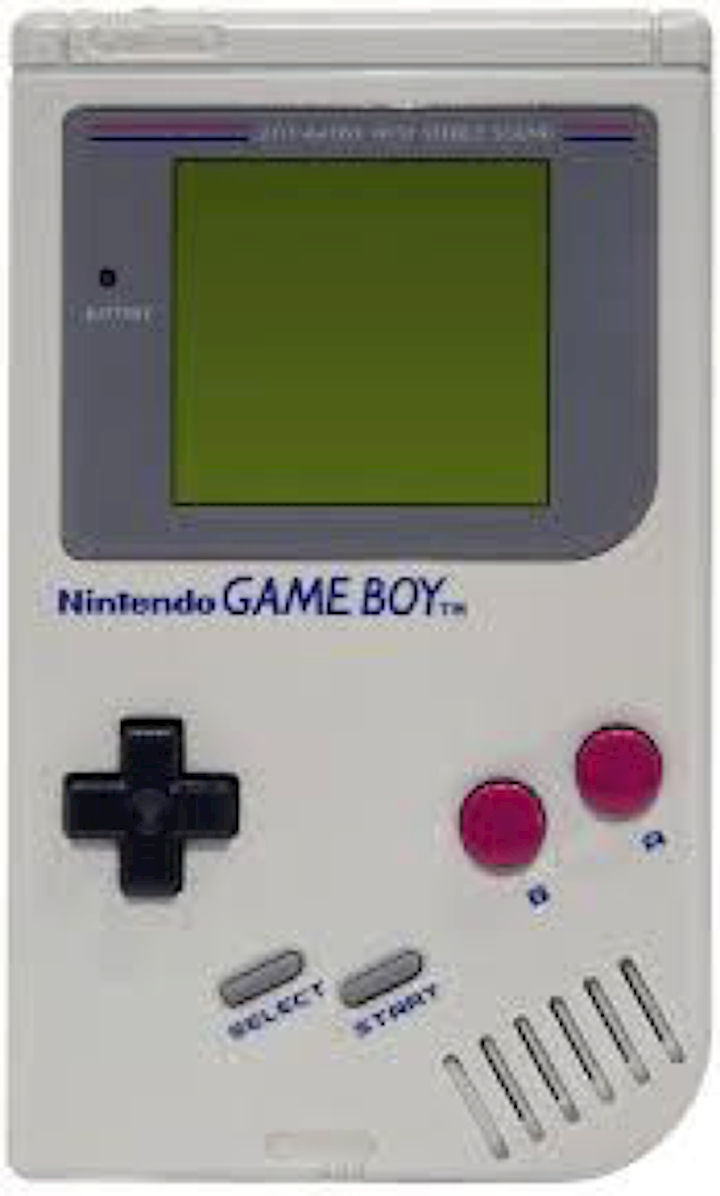

To begin, it is necessary to say a bit about how Chiptune got started. Although there were previous incarnations of the music style found in early video games, it is important to identify its real inception with the creation of the Nintendo Gameboy. According to the Center for Computing History, the first incarnation of the Nintendo Gameboy was released in April of 1989 in Japan, and later that same summer in North America.4 It was created by Gunpei Yokoi to be one of the first handheld gaming consoles available and has sold hundreds of millions of units all over the world since its release. The popularity of the Gameboy reflected a growing accessibility to technology during the 1980s and 90s. Personal computers and gaming consoles such as the Gameboy, became less expensive and therefore more available to a wide audience. As gaming technology became cheaper, new models of the same technology were being produced to “replace” old versions, so that the gaming companies were able to keep making a profit from the young kids and teenagers of the 1990’s. Much like any other human made technology, old versions of gaming systems became obsolete in the face of new versions with “better” capabilities.

Figure 1: Early Nintendo Gameboy

Something else happened though. Some Millennials became fed up with the consumerist demand by media and large corporations to continually “update” and purchase new technology despite having extreme financial debt and little career prospect. An urge to “take back” their childhood technology and make it theirs developed within the global gaming community. It’s important to note here that the technology was revolutionary for the time, but by today’s standards was very simple. This is important because, as the Millennial generation grew up, their sense of nostalgia for their childhood revived their interest in the old game consoles and of what potential lay within these limitations. In 2000, at the turn of the century, Johan Kotlinski, a gamer, hacker, and musician from Stockholm Sweden, developed the Little Sound DJ program (abbreviated often as LSDJ). The program was made so that when it is run on any old Nintendo Gameboy (earliest editions through the Nintendo DS), a user could “hack” the console and use it to create songs and soundtracks not originally created on the system. Instruments are created from the ground up, with endless possibilities for sounds and rhythms. With LSDJ and later programs like Nanoloop that also hack into the sound systems of antiquated gaming technology, Nintendo Gameboys became something more than their original purpose.

In cities like Philadelphia, groups of 8-bit musicians (as they are sometimes referred) began hosting gatherings (styled similarly to the early raves of 1960’s London) where they could show off their newest creations on the consoles. In fact, Philadelphia has become one of the major hubs for the scene. Many artists have relocated to the Philadelphia area because of the relatively large Chiptune community. The reason for this, I have learned, is because Chiptune is a subculture that arose out of the 1990’s grunge and synth-wave scenes, which also had large followings in Philadelphia. Moreover, Philadelphia is centrally located between New York City and Washington DC; both are cities that have large electronic dance music scenes. The question of where Chiptune started is the wrong question to ask, I found out. When I inquired, I was told that Chiptune didn’t really have a physical location—not at first anyway. Rather, the scene started online. This makes sense, as the majority of the original Chiptune artists were also active in online hacker and gaming communities. But just as fans of YouTube stars will often flock to “meet and greets” with their idols, so too did fans of Chiptune. It seems natural, then, that eventually live shows began to happen.

Akin to the Vaperwave musical movement, live Chiptune shows began to include a visual element. Much like going to see a concert at, say, the Wells Fargo Center in Philadelphia, musicians and composers in the Chiptune scene desired to have visuals projected onto the background of the stage to make the performance more exciting. The reason for this is simple; typically, a Chiptune show consists of different individual artists taking the stage for 30-50 minute sets. There is (usually, but not always) only one person on stage, as opposed to an entire band and equipment. A visualist will often collaborate with the Chiptune artist to create a sonic and visual harmony to make a more exciting performance for the audience. Interestingly, unlike other forms of live concert music, the visual artist will often appear on stage with the musician, “performing” their work of projecting images and video. The visibility of the visualist signifies that the scene isn’t just about the music but about the entire audio/visual and phenomenological experience. This show format became very popular, and in the early 2010’s Chiptune performances were being included in larger electronic music festivals. Artists like Eminem, Beck, and Ke$ha began including beats created from hacked gaming systems into popular songs. Chiptune artists began to be scouted by large gaming corporations to create soundtracks for new video games, and computer or gaming systems such as PlayStation and Xbox.

Dancing Values in Chiptune

Despite this huge expansion of the genre, Chiptune as a unique movement and sound has actually stayed somewhat in the shadows, and that’s the way the scene wants it. Still fighting the capitalist notions of our day and age, Chiptune craves to be original, to be unique, and to be outside of mass consumerism and creation for the goal of profit. Practitioners strive to maintain a sense of “do it yourself”, and they understand imperfection and mistake as a part of the genre. They reject the commercialization of the sound, and embrace small venue shows with relatively relaxed open mic segments, choppy transitions between songs, and visuals that sometimes freeze or glitch without warning.

I am often reminded of one show in Philadelphia that I attended during which the emcee casually talked to me before starting the show. At one point, she looked around the room and said “well I guess I should probably start”. In no rush, she walked up to the low stage, grabbed the mic, and began her opening, as if still conversing with me. “Holy shit guys, hi—is the mic on?” she asked as she squinted to find the person in charge of the sound. The casualness of this beginning seems so different from the grand entrance of a band in the Wells Fargo Center. There are no flashing lights, no signals for everyone to pay attention to the stage, just a short welcome and a few jokes, and the first artist takes the stage to quickly plug in his only instrument; his Gameboy.

The dance element seems just as relaxed, by which I mean there are no set rules for how to dance to Chiptune music. While there is a somewhat identifiable “vocabulary” of movement, there is no one strict dance form, like other forms of social dance. Rather, the movement typically resembles Graham St. John’s notions of “trance dance” within EDM music, wherein he speaks about the body’s surrender to a “fantasy of liberation5 ”. While some people bob their heads steadily to the down or upbeat, others move their arms frantically around their body, ignoring the pulse of the beat and choosing instead to let the music simply inspire their erratic movements. There are a few people in the Philadelphia scene that are known for their dance moves. They are the ones that stand the closest to the stage, and are often seen dancing with each other, doing moves that signal “inside jokes” within the community, such as moves from certain internet memes or online videos; shared knowledge in the community that signifies inclusion, exclusion, and belonging. The performers themselves, jumping around onstage or peering closely at their instruments, also are important in discussing how the body signifies values within the Chiptune community. To analyze these movements further, I will identify how they relate to and make visible each of the two core values that I have previously identified. My discussion will include examples from movements witnessed in the audience, as well as from performers on stage. Overall, I have found that many of the values that I have witnessed at chip shows (others including nostalgia, authenticity, and innovation) reflect general values associated with the Millennial generation, which is the core group age of the Philadelphia chip scene.

Individualism

According to a book on Millennials in the work force, “the largest cultural change in the West—and increasingly, the East—is the growth of individualism6 ”. Individualism is concerned, as it would seem, with the self, and the desire for individual success. It places the wants and needs of the individual over the collective success. This has led to radical changes in equality within gender and sexual identity.7 The notion of individualism might actually seem, at first, out of place within the context of Chiptune and other electronic dance music scenes. For example, St. John writes about Victor Turner’s idea about liminality within EDM dancing and moments where singular identity is lost to a larger collective identity, which is counter to the features of individualism.8 Chiptune, however, deals with individualism and collectivism in an interesting way. Turner’s ideas about collective consciousness are not completely absent in live chip shows; when the music is loud, and the room is dark, the moving bodies feel like they are all connected to each other. There is a mutual understanding and a dropping of identities. Personal boundaries are crossed; for example, the front of the stage will become crowded with movers. They bump into one another, a little at first, but then it develops into an all-out mosh pit. Close bodies moving in a dark area with pulsating music leads to, St John suggests, a loss of self momentarily, and it is within this undefined space and time that a transcendence occurs; transcendence that mirrors the drug induced hallucinations of the 1960’s drug culture9 . I have personally felt this transcendence during a live chip show when there is a particularly well-known or impressive performer on stage.

Figure 2: Philadelphia scene “regulars” dancing. Image by Marjorie Becker/Chipography, 8Static Festival 2016

However, within these moments of transcendence and collective consciousness, Chiptune still values individualism and uniqueness, which also manifests itself through movement. For example, one artist/chip enthusiast named Sylvester is known for his unique performance style on stage, his ability to quickly recognize fashion, and above all, his one of a kind dance moves, often performed while squeezed into the crowded audience. When I see him, it seems that a large part of his appeal to the group is his strong individualistic persona. His movements when he dances in the audience are quick and spastic, which goes against the slow steady beat of the rest of the audience’s movements. Another thing that sets him apart from the group is the use of his distal body parts. Typically, the neck, head, and upper back are the main body parts that get used within the general movement vocabulary in this crowd. The arms will become involved only to occasionally rise up to the ceiling or to the performer. The feet tend to both stay planted, and there is nearly never any movement of the hips or pelvis. Most often, the movement seems to be a sub-conscious reaction to the beat of the music.

Sylvester, though, circles his arms at the elbow quickly, while his legs and feet move him around the space with quick steps in a complex pattern. Sylvester is not a “formal” dancer, yet the mastery of his body suggests that he regularly breaks out into wild movement in celebration of hearing a song he likes. I get a strong sense that Sylvester is embracing his own individualism, that he is questioning, and pushing against, ideas about gender and race through his performance. Sylvester is, after all, one of the only African American chip enthusiasts who attends the Philadelphia shows. A slender young man, Sylvester’s moves play between masculine and feminine, strong and soft, echoing my previous statement about individualism’s relationship to re-assessing race, gender and sexuality roles. Again, I am reminded of Victor Turner’s notions about the liminality of identity within these alternative subcultures.10 Sylvester is able to navigate his body away from any normative positions and movement that are associated with the larger hegemonic culture.

Performers, too, are praised for their individualism during live sets. The Philadelphia chip artist who introduced me to the scene (whose stage names are Storm Blooper for musical performance and Enerjawn for visual work) is known for the absurd amount of equipment that he incorporates into each performance. Another chip artist who goes by the name Corset Lore squeezes on a corset before beginning her set. While she plays music from her Gameboy, she also sings, looking directly and pointedly out into the audience. Gender roles in her performances are therefore flipped, reversed, and rejected all within a 40 minute set. UK based Chipzel is another female chip artist who is well known for her performance style on stage. Particularly, she is known for jumping continuously on the stage, which might not seem like a unique movement—at first. But Chipzel will jump, and jump, and jump, nonstop, to the beat of her own music, for almost her entire 45-minute performance. This is an impressive act that engages the crowd, gets them to jump with her, and unites the audience in a singular movement. One Philadelphia based amateur Chip musician will often lie down on stage after he presses play on his Gameboy. His choice to be still, not interact with the audience, and to position his body as such seems to question the interaction between technology and the body, and the antiquated division between body and mind. It also allows for a re-configuration of the body on stage, and questions where the lines of performance begin and end. Interestingly, his choice to make his body “disappear” during his set was largely met with criticism from the audience during one performance. Some felt he was too new in the scene to be pulling “stunts” such as this. I speculate, however, that this disdain towards the performer’s actions actually has more to do with the function of these gatherings, which after all is the place where the culture, and the community, becomes physicalized from its internet presence.

Figure 3: Storm Blooper/ Enerjawn with equipment set up, dancing audience in background

The value of these individualized performances becomes apparent when one begins to understand how, exactly, a song is played on a Gameboy. Because of the technology, performers are actually very limited in what they can physically achieve on stage. This is because, like live instruments, the Gameboy needs to be “played”; buttons need to be pushed at the exact right moment, cables need to be rapidly changed from one “instrument” to the other. This is what sets Chiptune artists apart from regular DJs. While it is possible, as noted above, to simply press play and have an entire track run on its own, this, to many long time Chiptune enthusiasts, is a cop out. Individuality is important to the success of a performance so even the way in which buttons are pressed by the performer can symbolize their unique artistic identity. These examples are far from gimmicks done for applause or notoriety. Rather, they allow the artist to make statements with the body about who they are as people and as performers within the Chiptune community.

Investment

Perhaps the other most important value that I have found associated within the Chiptune community is what I call “investment”. While typically, the word investment is associated with money or capital gain, I use the term here in a slightly different way. Investment into the community and the growth of the Chiptune genre are of the highest value within this group, not simply through monetary investment, but through investment of time and energy. Investment is often reflected within conversations at live shows, such as someone talking about a new piece of equipment they got or the new song they have worked on for hours. It also means talking within the group about how to bring artists to the Philadelphia area from other areas of the world, so that they might invest some of their time and energy into the Philadelphia scene.

There is, however, another bodily phenomenon that I have encountered at live shows that illustrates investment as a value to the community: the “chip back”. This display of investment goes beyond what we put on our bodies. Rather, it invokes Sally Ann Ness’s notions of inscription of the body, wherein the body is not something to be read upon, not something that is on the skin, but is actually formed by culture, inscribed deeper than the skin.11 “Chip back” is a term I have come to know through my hours of on-site ethnographic research. This is the “C” curve of the back and bent forward neck that comes when an artist is performing on stage. Countless times, I have heard reference to someone’s “chip back” and how extreme it is. The forward curve of the upper back seems to signify something within this crowd. As an outsider, it seems that it is merely bad posture. But looking at many artists, it becomes apparent that almost all of them have the “chip back”, at least when they are on stage performing. There is both a simple, and a complicated explanation for this occurrence.

Figure 4: Chiptune Artist Niamh Houston AKA Chipzel displaying an example of “chip back”

While the performer is on stage, or even at home composing songs, they will often place their Gameboy and mixer onto a table, so when they are playing, there is a need to bend forward and drop the head so that the small screen on the console can be seen clearly. This is the simple, physiological explanation. The chip back is more complicated than this, however. From first-hand information passed onto me by many Chiptune enthusiasts in Philadelphia, the hunched back and internal focus on the music represents the artist’s interest and investment into the music. A song created with LSDJ or other software can take days, quite literally, to not only compose, but to create every sound and instrumentation from scratch. Imagine every time you were to write a song, say, for the guitar, you had to build the actual guitar to play it on. The amount of energy that this musical style takes is truly an investment. Not only that, but performers must also play all the “instruments” at once when they perform live shows. This means switching sounds and beats at the exact right moment, pushing the right buttons, having extreme focus and knowledge of their compositions. The chip back has come to be known as a sign of complete dedication to the music within the Chiptune community. The physical pain of being hunched over for hours is a sign of true artistry.

The C-shaped position of the 8-bit back isn’t isolated to the performers either. I have seen audience members in this concave position, bopping head and neck to the beat, their hunched shoulders and focused gaze reflective of their own investment in these live performances, and in the larger Chiptune community. There is something slightly grotesque about this body position, about the sweat that flings from hair and drips down backs and in the crowd, and I often get the sense of the audience being “there until the end”, of staying front and center amongst other slick and sticky bodies until the last chord is struck, no matter how tired or gross they feel. These are moments of true investment; moments when the community collectively rejects conventions of what is proper or attractive in favor of weird and complex expression of identity through movement. It is hard not to join into the sweaty mosh pit in these moments.

Another sign of investment that I see during live chiptune shows is the selling and wearing of apparel such as shirts, stickers, and buttons. At first glance, this might be a red flag; I have established previously the emphasis on anti-consumerism and anti-capitalism within this group. Why, then, is it so important for concertgoers to purchase and wear these things? Why is spending money a good thing, when such a large part of the scene rebels against consumerist notions? Even the entry fee, which is by donation, has a sticker reward for those that pay ten dollars or more. At first, this seems like a large contradiction. But digging further into the matter, I found a completely different explanation.

The investment, I was told, is not about the money that has being spent. Rather, it is about fans using their own bodies as a space to advertise their favorite artists. It is yet another way that fans can invest their own facility, that is, their body, into the community. When they wear the T-shirts and stickers, it’s as if they are giving free publicity to the scene and to the artists. They are more than for the prestige of the concertgoer to show that he or she was in attendance at a show; they function as something much deeper in terms of investment. The artists as well, display investment through selling apparel at live shows. Often times, T-shirts are created and sold by an artist at the request of the fans, not as it would seem, to make a profit. This means that the artist must invest their own time into designing the T-shirts, and their own money into producing the shirts prior to the show.

Conclusion

At first glance Chiptune music may seem unrelated to the body; the music is generated by machines, shared online, and relies heavily on technology. In actuality, though, there seem to be a number of factors at play within the community that deal directly with the body. Body politics, politics of the entire scene in general, can often be witnessed at live Chiptune shows. As of late, there have been fewer and fewer of the “regular” crowd attending the monthly Vox Populi shows. I attribute this to rising numbers of people in the group finishing undergraduate and graduate programs, getting full time jobs, beginning their careers, moving away, or starting families. While everyone is still “into” Chiptune, they all seem to have less time to meet every month. Still, though, the scene lives on. New albums are being produced every few months, and recently, the lineup for the massive Washington D.C. based MagFest (Music and Gaming Festival) was released, and includes a large number of Chiptune artists, many of them from Philadelphia.

Many fans and artists from the Philadelphia area were very anxious when speaking to me about the Chiptune community. At first, I didn’t know why. But then, after a year of attending shows and becoming very integrated into the scene myself, I realized that the anxiety came from a place of protection. Alternative scenes such as this are so often a safe haven for people who “don’t belong” anywhere else. Chiptune has become a place of free expression without persecution, it offers a space to explore other identities and roles, a space to transgress, and sometimes, like recently, a space to heal from the trauma of the outside world. It is a scene that is ever changing, ever evolving, and as I am reminded over and over again from our ostentatious emcee, “totally, fucking awesome.”

1. “Home page”, Vox Populi, 2018, voxpopuligallery.org. back to text

2. Andy Bennett and Richard A. Peterson, Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2004), 1. back to text

3. Sally Ann Ness and Carrie Noland, Migrations of Gesture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2008), 11. back to text

4. “Nintendo Game Boy”, Center for Computing History, 2018, www.computinghistory.org.uk back to text

5. Graham St. John, "Liminal Being: Electronic Dance Music Cultures, Ritualization and the Case of Psytrance", The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music (2014): 250. back to text

6. Eddy Ng, Sean T. Lyons, and Linda Schweitzer, Managing the New Work Force: International Perspectives on the Millennial Generation (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Ic., 2012), 4. back to text

7. Ibid. back to text

8. St. John, 151. back to text

9. Ibid, 153. back to text

10. Ibid, 154. back to text

11. Ness and Noland, 9 back to text

Works Cited

Anderson, Tammy L. Rave Culture: The Alteration and Decline of a Philadelphia Music Scene. Philadelphia PA: Temple University Press, 2009.

Becker, Marjorie. “8Static Festival 2016: Day 2.” Chipography 2016, http://www.chiptography.com/?p=3837, figure 2.

Bennett, Andy, and Richard A. Peterson. Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2004.

Blake, A. "Game Sound, An Introduction to the History, Theory, and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design." Journal of Design History 22, no. 3 (2009): 294-95.

Bongotromme, Bjørnar. “Untitled." Facebook, 2014, https://www.facebook.com/Chipzel/photos/a.10153339170112662.1073741826.160094092661/10153339174877662/?type=3&theater, figure 4.

Collins, Karen, Bill Kapralos, Holly Tessler, and Leonard J. Paul. "For the Love of Chiptune." The Oxford Handbook of Interactive Audio, 2014.

Edward, Ralph. “Enerjawn, Magfest DJ Battle 2016.” Facebook, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10153408533432197&set=pb.509937196.-2207520000.1522256309.&type=3&theater, figure 3.

Ferreira, Pedro Peixoto. "When Sound Meets Movement: Performance in Electronic Dance Music." Leonardo Music Journal 18 (2008): 17-20.

Huq, Rupa. Beyond Subculture: Pop, Youth and Identity in a Postcolonial World. London: Routledge, 2006.

Ng, Eddy, Sean T. Lyons, and Linda Schweitzer, eds. Managing the New Work Force: International Perspectives on the Millennial Generation. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Inc., 2012.

Ness, Sally Ann and Carrie Noland. Migrations of Gesture. Minneapolis: Unicersity of Minnesota, 2008.

Nintendo Gameboy. "The Centre For Computing History." Nintendo Game Boy. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Oct. 2016.

Populi, Vox. "Vox Populi: An Artist-Run Space in Philadelphia." Vox Populi. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Oct. 2016.

St. John, Graham. "Liminal Being: Electronic Dance Music Cultures, Ritualization and the Case of Psytrance." The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music (2014): 243-60.

St. John, Graham. Victor Turner and Contemporary Cultural Performance. New York: Berghahn, 2008.

Thomas, Douglas. Hacker Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2002.

Tomczak, Sebastian. "Authenticity and Emulation: Chiptune in the Early Twenty-First Century." International computer music conference proceedings, 2009.

“Untitled.” The Center For Computing History, www.computinghistory.org.uk/det/4033/Nintendo-Game Boy/, figure 1.