On a brisk, sunny November afternoon in 2018, five undergraduate choreographers at Reed College in Portland, Oregon led ten people on a journey through the College’s grounds and buildings. The experience fell somewhere between a campus tour and a series of site-responsive dance performances. Making several stops over the course of an hour, the performance highlighted public expressions of dissent mounted on Reed’s campus, spanning from the late-1940s until 2001. This multimedia documentation of the project aims to share one example of how university/college dance classrooms can prepare students to be artists, citizens, and public intellectuals.

What appears below is, first, background and context for the performance, followed by a virtual experience of it through text, photo, and video. The next segment features students’ reflections on their work, presented via transcripts of audio-recorded conversations held after the production. Finally, I reflect on this experience from the teacher’s point of view, offering some thoughts on dancer citizen pedagogy.

Background and Context

I created this project with five Dance majors at Reed College: Morgan Meister (’19, she/her), Erin Lauderdale (’19, they/them), Hannah Jensvold (’20, they/them), Alli Fatone (Dec. ‘19, they/them), and Maya Nájera Evans (Dec. ‘19, they/them). They were enrolled in a special topics choreography class that I taught as a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Dance Department during the 2018-19 school year. I decided to organize my course around parades, protests, and processions as a way to connect my scholarly research on carnivalesque dance forms in New Orleans to my artistic research in contemporary dance and theater. This course fit into Reed’s Dance curriculum, which is based in contemporary dance in global contexts, as it invited students to expand their approaches to making dances beyond the proscenium stage without asking them to replicate an actual parade, protest or procession. We considered, among other elements, the ways in which these techniques for moving people through space assume specific roles for spectators; chart routes through space; make use of repetition; and deploy visual symbols and text. I asked students to think about parades, protests and processions as choreographic acts that have been and can be used for different and sometimes opposing purposes, such as the imposition of state control and organized resistance against oppression. Students’ choreographic studies translated crucial questions about each mode into site-responsive performances that activated chosen on-campus locations with movement, text, and sound.

For example, during the unit on processions, one group created a durational journey through the library while another led the class on a sensory experience of Reed’s on-campus canyon. Both performances were motivated by the same prompt: create a processional dance that leads your audience along a predetermined path, linking several sites together, over the course of at least 20 minutes. I asked students to carefully consider where their procession started and ended, and what stops it would make along the way. Fatone and Meister’s procession through a dusty, neglected corner of the library’s stacks highlighted the changing pace and materiality of knowledge production as the embodied process of conducting research shifts from lifting heavy books off of metal shelves to mouse clicks and keyboard taps. Jensvold, Lauderdale, and Nájera Evans took a more personal approach, immersing us in Reed’s capacious on-campus canyon as a retreat from the school pressures and life challenges awaiting them at the end of the trail. Both groups’ experiences in crafting a durational, ambulatory experience in relation to on-campus histories, both conceptual and personal, primed them for the next unit on protests.

When designing the procession project, the first group assignment of the semester, I provided very specific guidelines. However, when beginning the unit on protest, I asked the students to collaborate in designing their choreographic output. This was in part determined by the fact that the class wanted to devise a performance for an annual student-led arts festival, Reed Arts Week, which fell during our unit on protest. This pedagogical shift was also possible because, after two months of working together, the six of us were ready to operate more democratically as an ensemble. Therefore, as a group, we discussed what kind of choreographic assignments could be inspired by protests. Students expressed a desire to work with a large number of people, and yet, did not want to organize an actual protest. They felt that doing so would be disingenuous. While our class explored the ways in which politics and aesthetics are often inseparable, the fact remained that, if these five dance students were to organize a protest, the impetus would have been somewhat artificial, disconnected from a broader movement, and ultimately a one-off event. The students understood enough about protests to know that an isolated instance, as a class project, would not actually deepen their understandings of the choreography of protests in a meaningful way.

Furthermore, fall 2018 was the first semester in their undergraduate careers that saw a relative absence of student-led unrest at Reed, and the choreographers were understandably cautious to re-engage. Starting in fall 2016, a vocal and visible contingent of Reed students, led by group called Reedies against Racism (RAR), began demanding less Eurocentric curricula and institutional disinvestment from private prisons. The many actions taken by student protestors included occupying then President John Kroger’s office and the admissions office; sitting in front of professors as they lectured to hundreds of Freshmen enrolled in Humanities 110; and disrupting that same course with chants, and even a with the time-honored Reed tradition of a “noise parade.” RAR ultimately saw several but certainly not all of their demands met. For example, in fall 2018, when my choreography course convened, Reed rolled out the new Humanities 110 curriculum, designed to de-center its historically Eurocentric focus. However, the College continues to invest with Wells Fargo, a bank with significant financial interests in the prison industrial complex. The juniors and seniors in my class had spent many hours of their undergraduate careers embroiled in a campus climate dominated by protests and placed under a national media microscope. The history was too near, emotions remained somewhat raw, and as a heterogeneous group, not all shared identical views on what had transpired.

For these reasons and more, mounting a protest did not seem appropriate as a class assignment. (Would it ever be?) But the question remained – how might the choreographic techniques of protest inform our dance making? We read several Dance Studies texts on the topic,1 researched recent protests that featured dancing bodies as a way to disrupt conventional uses of public space,2 and discussed it during a virtual guest visit from choreographer, writer, and organizer Lela Aisha Jones.

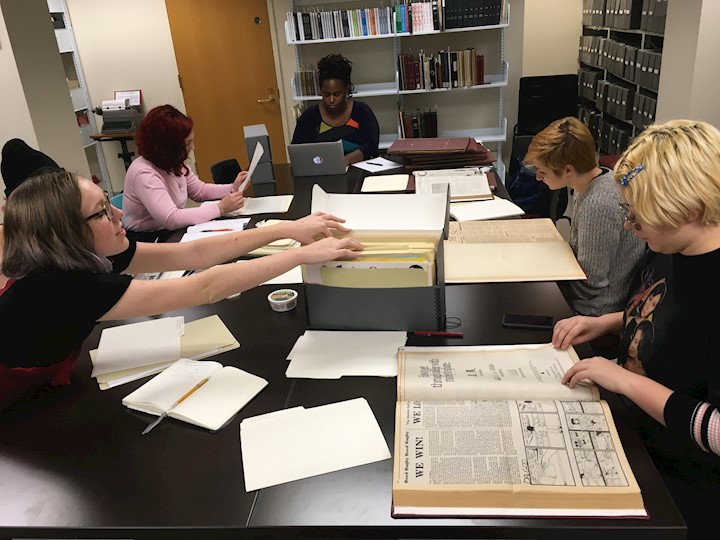

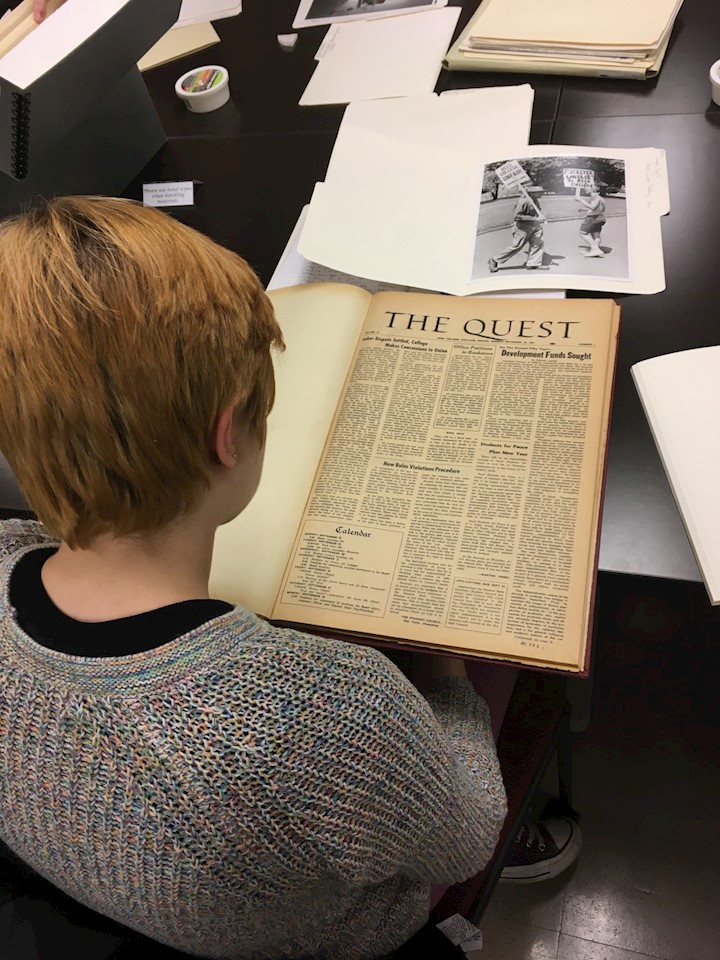

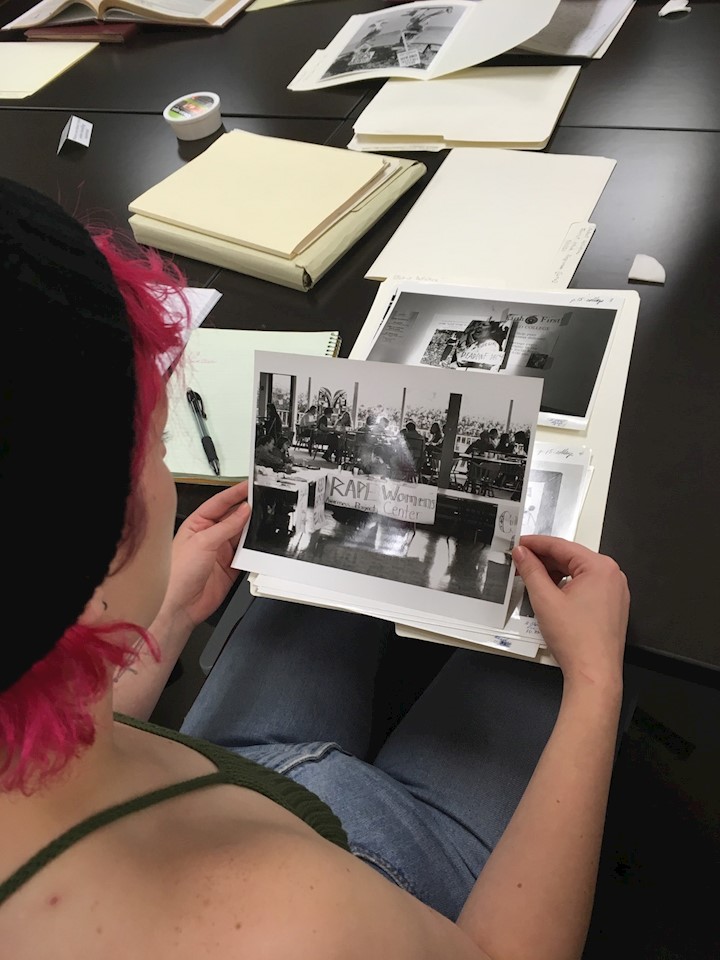

Ultimately, the students and I decided to create a site-specific performance that highlighted lesser-known episodes of resistance on Reed’s campus. We worked with the College’s Special Collections, guided by archivist Maria Cunningham, to identify historic sites of protest. I asked the students to limit their research to twentieth-century events (including the events following September 11, 2001) because I wanted to encourage them to dig beyond their recent memories (and even beyond much of their lifetimes) in order to understand the activity that had dominated so much of their undergraduate years within an even deeper historical context than they already did. They leafed through archived editions of the student newspaper, the Quest, and editions of Reed Magazine, published by the Office of Public Affairs; perused stacks of photographs; and read through letters, transcribed oral histories, and other print materials. The group began to see, with sharper focus, a long history of dissent at Reed.

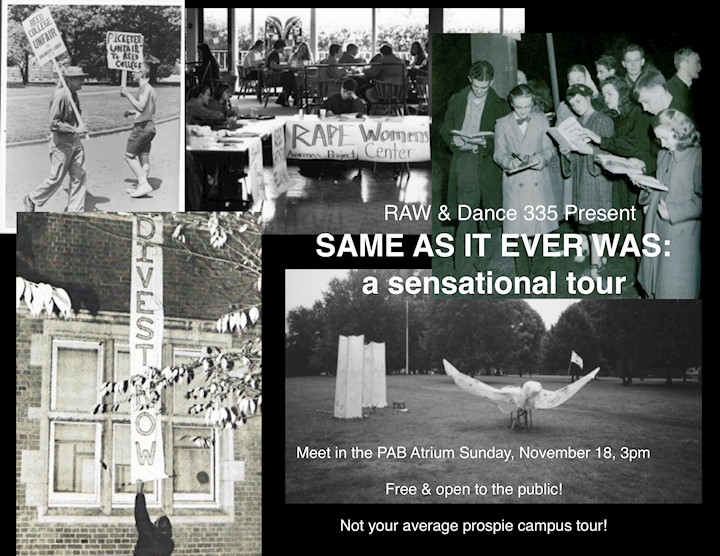

Each choreographer chose one event as the focus on their choreographic research and then made choices about how to activate the location(s) in which that event occurred through movement, text (spoken and written), physical materials, and even food. The result was an ambulatory journey through five instances of opposition to institutional and state power ranging from 1947 to 2001. The students entitled their piece, “Same As It Ever Was,” nodding to their growing sense of the cyclical nature of institutional and social change, as they compared earlier protest examples to their recent experiences.3 The ambulatory performance toggled between distant and recent histories, especially since several tour locations have been recurring sites of civil disobedience through the decades (such as the flagpole and the College President’s office, located on the third floor of the main administration building, Eliot Hall).

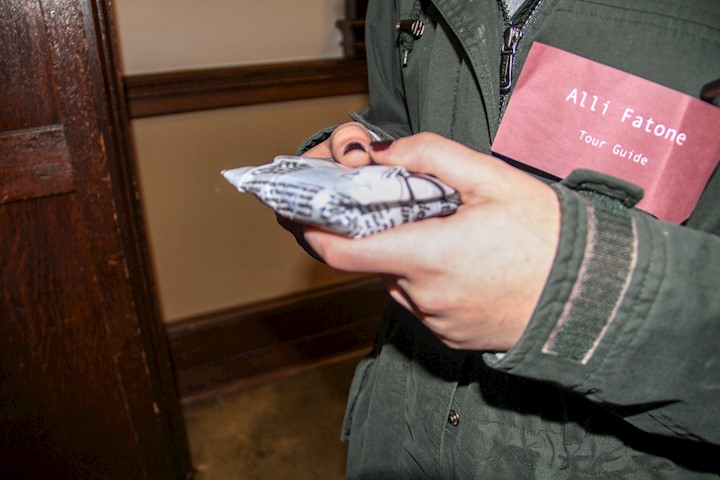

We decided to adopt the campus tour format—somewhat earnestly, somewhat satirically—as a way to move the audience from one site to another. Students printed replicas of tour guide name tags and addressed their audience members as “prospies.” Prospie is the affectionate shorthand for prospective Reed students who can often be seen in packs, with parents and siblings in tow, following backward-walking undergraduate guides. The tour was a convenient conceit, but in my post-performance conversation with the artists, I realized just how appropriate it was. We began to see campus tours as a technology for perpetuating (and rewriting) the narrative of an institution, and a choreographic technology at that. The students’ negotiation between tour and protest scores revealed how these forms of student-led social choreography at Reed repeatedly stage embodied narratives about the College that sometimes align but more often collide.

- PERFORMING ARTS BUILDING ATRIUM: WELCOME

Moran Meister greeted the audience members, who had followed the flyer’s directive to gather in the Performance Art Building atrium. She gave a brief overview of the tour and directed everyone out the doors.

- MULTIPLE SITES: ESTABLISHING THE WOMEN’S CENTER (1979-1990s)

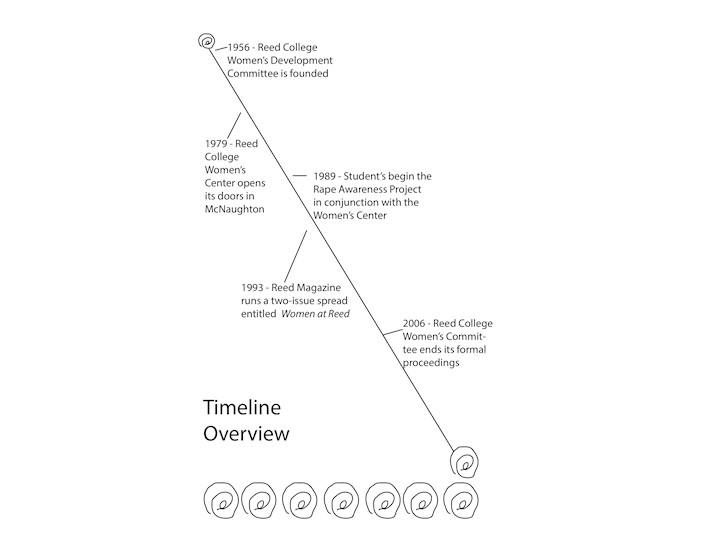

Meister’s piece was a mini-tour within the tour. She led the audience to several locations as she and other choreographers narrated the long history that led to the existence of the current Women’s Center. Walking backward like a Propsie Tour Guide, Meister began by pointing out the first dormitory dedicated to female students (Anna Mann, opened 1920), explaining the Women’s Development Committee (founded 1956), all while leading the group to McNaughton Hall.

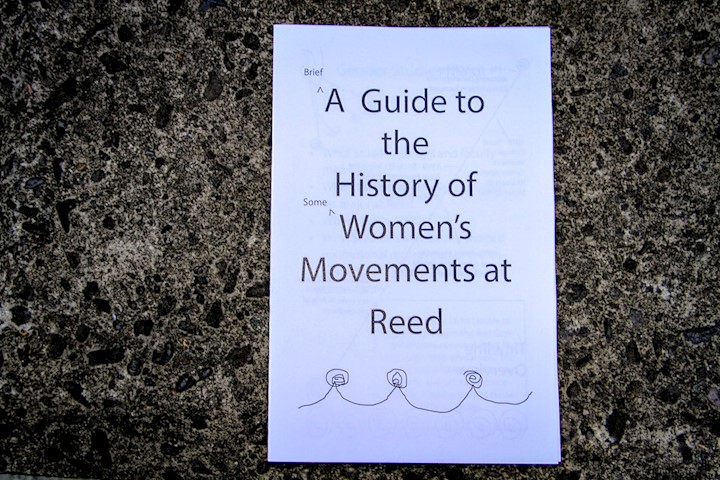

In front of McNaughton, Hannah Jensvold told tour-takers about the founding of the first Women’s Center there in 1979. They spoke into a microphone, a nod to the open mic nights that were a central piece of Women’s Center social activities. From there, Meister led the group across campus to the current site of the Women’s Center, in the basement of the Gray Campus Center. Along the way, the audience encountered other student performers who narrated key points in the Women’s Movement at Reed. At the end of the tour, audience members received a ‘zine: “A Brief Guide to the History of the Women’s Movement at Reed College.” Again, the format mirrored the history, as ‘zines have been and continue to be an important way to circulate information and stories amongst students involved with the Women’s Center.4

- FLAGPOLE: POST-9/11 DEMONSTRATIONS (2001)

Alli Fatone guided everyone from the Women’s Center to the flagpole, erected on the Great Lawn that stretches out in front of Reed’s main administration building, Eliot Hall. Along the way, Fatone told the group about on-campus demonstrations that followed the events of September 11, 2001, which included a struggle between students and Campus Safety Officers regarding the display of the American flag. A group of students routinely and covertly hung the flag upside down, while officers insisted that it be flown right side up (and always at half-mast).5

Fatone invoked this history in multiple ways. As the group approached the flagpole, the five student dancers walked ahead of the audience and began a simple choreographic sequence that began and ended with a salute. Next, while the dancers removed small cloth American flags from their pockets and began to desecrate them in various ways (writing on them, stuffing them in their mouths, stepping on them), Fatone asked the audience to recite, in union, the “Pledge of Disobedience” that they had authored and passed out on slips of paper:

I pledge disobedience,

to the inverted flag,

of the United States of America,

and to the republic for which it stands,

one nation,

under Bush,

divided by terrorism and fear for all.

- ELIOT HALL: ANTI-APARTHEID SIT-INS (1986) and BLACK STUDENT UNION SIT-INS (1968)

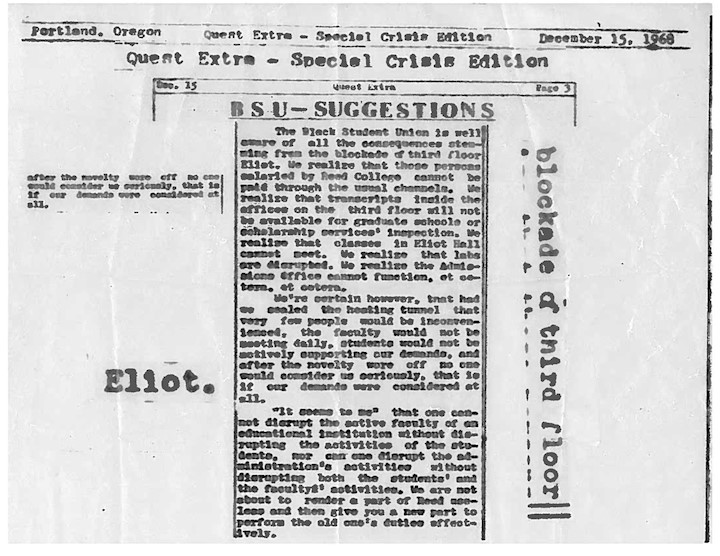

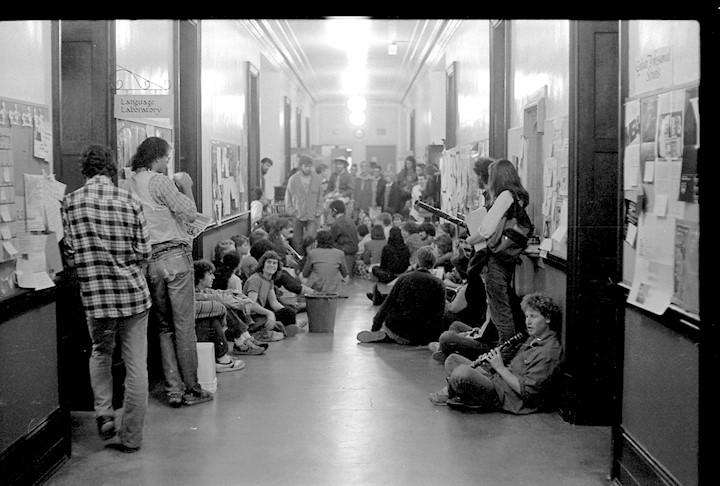

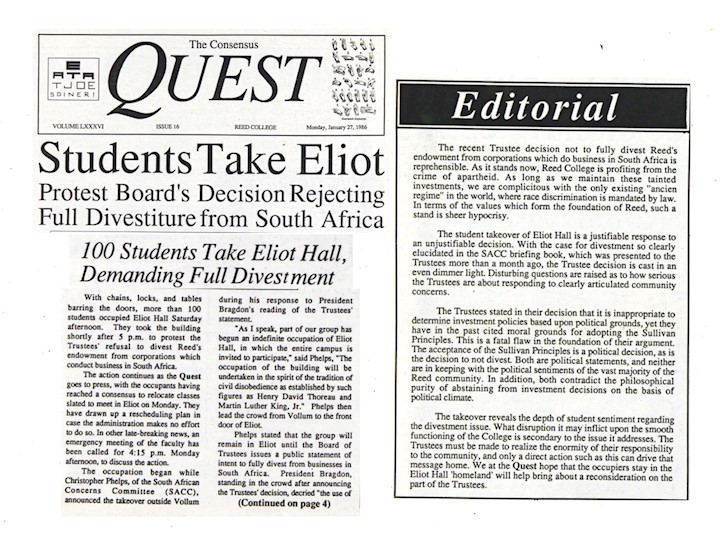

As audience members folded up their slips of paper, Maya Nájera Evans invited them to begin walking to the next tour stop: the third floor of Eliot Hall, where the College President’s office resides. Along the way, Nájera Evans detailed the events of a 1986 student sit-in demanding that Reed College divest from corporations tied to South Africa. Their demands joined increasing outcries worldwide that denounced South African apartheid. The sit-in began with hundreds of students forming a human chain that wrapped around the perimeter of Eliot Hall. As part of their organizing, the 1986 students invited alumni to speak about their experiences in a 1968 sit-in organized by the Black Student Union to demand, among other things, the inauguration of a Black Studies program.6 (Reed still does not have one, but Fall 2018 marked the inaugural semester of the Comparative Race and Ethnicity Studies program.)

Once everyone made their way to Eliot Hall’s third floor hallway, Nájera Evans instructed the group to form a single file line so that they could each receive a cookie wrapped in wax paper. Nájera Evans had printed the wax paper with articles from the Quest stating the demands of the 1986 and 1968 protesters.

Once all cookies had been distributed, the dancers began a simple choreography and implicitly invited all to join: the first person in line began weaving in and out of every subsequent person in line, until reaching the end. The movement was then repeated by the next person in line, and then the next, and so on.

- LIBRARY: TOM KELLY AFFAIR (1947)

Next, Hannah Jensvold assumed the role of tour guide, directing the group down the stairs/elevator, outside of Eliot, and toward the main entrance to the Eric V. Hauser Library. En route, Jensvold related the main events of what they came to call the “Tom Kelly Affair.” On February 6, 1947, World War II veteran and Reed College student Tom Kelly was arrested by Portland police for failing to carry his military discharge papers. At the time of arrest, he was reading a book of poetry by Percy Shelley outside the library. The next night, Reed students protested the unfair detainment of their classmate by standing outside the library and, under the moonlight, reading aloud poetry by Percy Bysse Shelley. As Jensvold told the audience, the story received media coverage throughout the nation and the Portland police’s disregard for justice and mistreatment of Kelly captured the attention of the ACLU.7

Jensvold directed the audience to travel back to 1947:

“Now, as we stand in front of the library, underneath the street light, today, I invite you to close your eyes, feel the same cool crisp air of the February night, and listen.” On that cue, all five performers began to walk slowly through the standing crowd, whispering lines from Shelley’s poem, “The Waning Moon:”

And like a dying lady, lean and pale,

Who totters forth, wrapp'd in a gauzy veil,

Out of her chamber, led by the insane

And feeble wanderings of her fading brain,

The moon arose up in the murky East,

A white and shapeless mass.

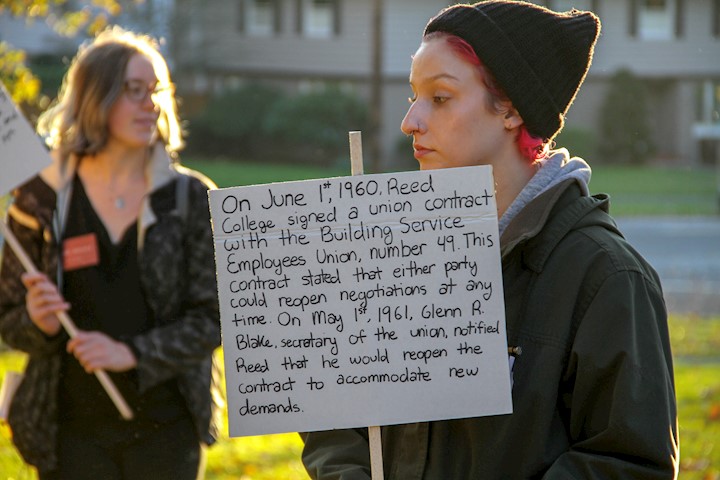

- WOODSTOCK AVE. ENTRANCE: BUILDING SERVICES EMPLOYEES UNION STRIKE (1961)

Erin Lauderdale assumed the role of guide for the final leg of the tour. They led the group to a nearby grassy area that flanked the main vehicular entrance to Reed’s campus from a major thoroughfare, Woodstock Avenue. Lauderdale had pre-placed five picket signs in a circle, where the dancers retrieved them. Each sign contained a hand-written sentence or two detailing an aspect of the Building Services Employees Union Strike of 1961.8

The audience stood on the sidewalk and watched as the dancers marched in a circle, pumped their signs in the air, and shouted, “Reed College! Unfair!” One by one, the dancers stepped into the center of the circle and read aloud the facts printed on their signs. After each recitation, their fellow performers joined them in a call and response chant:

“Reed College!”

“Unfair!”

In a comedic about-face, Morgan Meister snapped from determined picketer to cheery guide and informed the audience-turned-prospies that their campus tour had concluded. She welcomed them to follow her back to the Performing Arts Building or to disperse from the College entrance. And with that, “Same As It Ever Was” concluded.

Student Reflections

On Tuesday, November 20, during the first class meeting after our Sunday performance, the student choreographers and I sat down for an audio-recorded conversation about their work. They each arrived with questions for each other, and consented to have the dialogue audio-recorded, in the hopes that their work would be shared publicly.9 I have arranged the following excerpts to address two broad themes that emerged during our conversation—namely, the role of dissent in both the campus tour and institutional memory—before detailing each choreographer’s reflection on her/their work. The final segment of the transcript presents the students’ reflections on what dance has to offer political movements.

The Campus Tour

Erin Lauderdale: How did our protest tour impact the audience differently than a prospie tour would have?

Morgan Meister: I think that one thing that was really interesting - when I was thinking about and writing the prospie tour introduction-ish thing as a protest tour - is the different histories of Reed that are given. Because on a prospie tour you learn so much about the College, and you learn about the parts of the College that they you want you to learn about, and they don’t ever really—or at least on my prospie tour- they definitely did not talk at all about dissent or student opinions. And I think that our protest tour really enriched that history. The lesser-told but just as important institutional history of Reed. Or at least certain aspects of it.

Hannah Jensvold: Yeah, I would agree with that. And I also think, as it was happening, I was thinking a lot about how the histories and the image that a lot of admissions other official College office message about Reed often does kind of include this idea of dissent. “Oh, because Reed is different!” and “Our students do this.” But the way that that is sort of sanitized, I guess, that it’s really interesting that these stories of dissent that we talked about are not something that you would see in that context.

Alli Fatone: I think particularly the Eliot protests that are so present throughout the history of the College, it’s surprising. I mean, I get why they wouldn’t want to tell that on a prospie tour, students have not yet financially committed to the school, to put it nicely, but I also—it feels ingenuine to not include protest as a significant part of student life, or at least of some students’ lives.

Institutional Memory

MM: It’s interesting to me though that the idea of these histories of protest as institutional memory because we learned about them from the archives. They’re archived and they are an institutional memory in that they were recorded by the institution. So obviously they’re important to someone, somewhere. It’s not just us or people who are wondering the same questions as us, and why don’t those people get a say? I don’t know. I do know, but it’s just interesting that we found all this stuff out from the Quest and from Reed Magazine instead of like some weird student publication that was posted on the wall without any sort of check or anything, you know?

HJ: It also made me wonder about how maybe the role of the Quest has changed and maybe partially because of social media. Because the things that Alli was talking about happening in the Quest, these back-and-forth discussions are something that I think at Reed today would happen—

AF & HJ: —on Facebook.

HJ: Yeah, in a group in a comment section. I honestly don’t feel like I know really what the role of the Quest is today, but from our exploration, and even seeing the days that it had outside advertising and stuff, it seemed to be a little bit more of an autonomous voice.

RC: That’s really connected to larger questions too about, what is the role of print media in the age of social media? And that’s one really interesting observation from this process, looking back [at] how a student newspaper used to function and also the fact that because it was published there, these debates were recorded there, that it’s part of the institutional memory, the archive that we can go find, and what will that – will those conversations that happen on Twitter or Facebook now be findable, archived, collected as part of the institutional memory in the same way, for better or for worse?

EL: And also I feel like it’s a question of—I don’t know. In Facebook comment sections, no one—I mean there isn’t really a filter of someone publishing them besides yourself. […] If FB comments are taking the role that the Quest used to, how does that change whose voices are heard and how legitimized they are?

MM: They used to have this publication called the Student Body Handbook, and it was put together by a group of students every year, that was appointed by Senate, actually. And they would collect all these stories, oral histories, basically—tips and tricks and all of these things. And in a lot of Student Body Handbooks there is a protest section. The last Student Body Handbook was published in 2015, which was when we [seniors] first started and since then there hasn’t—I don’t think there has been one, has there?

HJ: No, they tried to do one this year but it just didn’t really happen.

MM: Yeah, so again, this idea of print media, and that going by the wayside and these knowledges and informations [sic] becoming less accessible to us in a way. I wonder how that shapes how we conceptualize protest and dissent at Reed, as students, not receiving that information, versus the ones who previously had [Student Body Handbooks].

HJ: Yeah and as those sources of print media that were coming from students about student life and student issues—I think by being print media, it probably afforded them a certain kind of legitimacy. It makes me think a lot about—if students don’t have those spaces as much that feel as legitimate to pass along these oral histories and traditions, what power that gives the administration to retell those histories and traditions and shape them differently than the students might?

[…]

MM: Talking about the prospie tour brings me back to the sit-in of Eliot that happened in the admissions office. And how one of the big things during those couple—one, two weeks? How long? I can’t remember.

HJ: I think it was two weeks.

MM: Yes I think so too. During those two weeks, [what I remember] was everyone being like, “But the prospies! The prospies have nowhere to meet to go on these tours!” And all of these things. And it was like the worst thing that we could have possibly done at the time. […] It was just like this giant point of contention where we were like, “Well, let the prospies come talk to us,” and they were like, “Absolutely not,” and I think they ended up canceling some of the prospie tours—

HJ: —and they were also redirecting them into the chapel so they wouldn’t see us.

RC: This conversation is making me realize how appropriate the tour format was for this project. At the time, […] I just didn’t think about it that much. Tours as this technology for the narrative of the institution that actively avoids the history of dissent. And so reappropriating the tour to explicitly talk about the history of dissent is in and of itself a pretty radical move. I didn’t really realize it, it just seemed like a convenient way to move people around. A conceit, I guess. But you all knew this. I’m brand new. Even if you didn’t know you knew it, you knew it.

Stop(s) #1: McNaughton Hall, Gray Campus Center, and more; Women’s Movement (1956-present) – Choreographer, Morgan Meister

AF: I have a question for Morgan. So your portion of the tour was like a micro-tour within the tour. How does this micro-tour aspect add to how we investigate and explore the movement that led to the creation of the Women’s Center?

MM: When I was considering how to best lay out this long history of women’s movements on Reed campus one thing that came to mind, probably because of my previous research [on Haitian rara], and it was the procession. This idea that the beginning matters, and the end matters, and the path that we take to get there matters. And so the micro-tour informational format was really playing into the idea of a sustained movement. Especially here and with the history we were exploring, having some kind of durational procession where you learn little pieces about the way things are now and how we get to the point that we are at now. Especially with women’s movement, so much of it built off of everything else. It wouldn’t have even been possible if Anna Mann [Residence Hall] hadn’t been built in the 1920s, to make it more accessible for women to go here, which I did talk about in the very first part of the tour. Then we get to McNaughton [Hall] and it’s the first site of the Women’s Center, but then we go back in time to how did this even become something people were thinking about, right, like [with] the Reed College Women’s Committee. And then looking at the ‘90s spread in [Reed Magazine] that was very apologetic for never having talked about women before, and then finally talked about women, and how that empowered us to keep going, in a way. Using the processional format that was more durational and longer helped illustrate the fact that this has been happening since the very beginning of the College, and women and oppressed gendered people have been fighting for equal rights, and Reed College is no different than the greater world. That’s hopefully what the audience got.

Stop #2: Flagpole; post-9/11 demonstrations (2001) – Choreographer, Alli Fatone

HJ: I have one for Alli. I was wondering what it was that you most wanted to convey to the audience or get the audience to pick up [on] with the contrast between the flag desecration and the pledge of disobedience […]?

AF: I think that what I was trying to get across was the dissonance of opinions that happened after 9/11 on the campus, mostly through—just represented in the flame wars in the Quest, and that there were so many that spanned over a month. And the week of the flag going up and down I think really characterizes that time, or what I understand of it at this point, obviously I wasn’t there. […] Yeah that dissonance of allegiance to the state and disallegiance to the state—if that’s a word, I don’t think it is—that tension on campus, regarding that.

HJ: I think something else you captured really well through those moments was also this tension too between mourning and—how patriotism and mourning that moment and blame and how it’s all a very difficult, complicated way to figure out how those fit together and how to reconcile some of it.

RC: Can you say a little bit about the choreography that you had everyone do at the flagpole?

AF: Yeah, so that came out of another piece in the exact same site that was kind of, I was thinking about …. It was at a flagpole that is right in front of the main administration building on campus. My prior piece was thinking about the connection between state and education, which ended up being relevant to this project as well. So I took the very beginning piece of that, which was, we all start at salute to the flag and slowly waver out of it into fluid bodies while our hand is still at salute and then stiffen back up. In this piece [“Same As It Ever Was”], I was thinking about the dissolving of rationality, kind of, and the dissolving of sense, and how nothing makes sense, and it all kind of comes back to stiffness, and an idea of stability.

Stop #3: Eliot Hall, Third Floor; Black Student Union sit-ins (1968) and anti-apartheid sit-ins (1986) – Choreographer, Maya Nájera Evans

Maya Nájera Evans: So there has [sic] been like a million occupations of Eliot over the past century, but the two that I was mostly focused on was this one that happened in 1986 which called for Reed to divest from companies who had interests in South Africa, especially with apartheid going on, so they were asking [Reed] to divest from companies who had apartheid interests. And this actually led to a fast, so students fasted, I don’t know for how long. They actually fasted with Lewis and Clark [College] students. Lewis and Clark actually did divest; Reed didn’t. During their occupation of third floor Eliot, they had some alumni come and talk about an occupation that happened in 1968 which was done by the Black Student Union, and it asked professors and administration to create a Black Studies program, which they didn’t do. And [the administration] actually called [students’] calls for their proposed syllabi, “Soul Food 101.” And so after they did that, the Black Student Union students crashed a trustees’ dinner and ate their food. So there’s this really interesting connection to food throughout all this. They ate the trustees’ food and then later they fasted, and then during the protests that I was a part of, if people weren’t actually occupying, one of the ways they supported the occupation was by bringing just a crap-ton of food. So there’s just, like, food everywhere.

So what I ended up doing was I bought these really horrible cookies from Trader Joe’s. They tasted disgusting. They were gluten free and ginger and weird. And I wrapped them in wax paper where I had printed the demands of the Black Student Union as well as the demands of the students protesting the South African interest companies. And I handed them out to people, to the people who attended the tour. And then I asked them to weave in and out of this line that we had created, and I just sort of wanted to bring in this feeling of closeness and compactness that happened during the protests and during the occupation as well as this connection to food. Yeah. Yeah, and then to get to the food, you had to unwrap, but then you had to unwrap these articles [published in the Quest] that were talking about fasting so you had to really choose on —you had to really think about what you were doing when you unwrapped these cookies. […]

And all of my information I got from the archive here. I went into the Quest archives and I basically looked up articles from the Quest because I couldn’t find anything else. There didn’t seem to be any other coverage in the Reed archives other than Quest articles on those events.

RC: And, Maya, that choice to have everybody in a line and then people weaving through—and so the audience was doing that too, they were involved in your choreography—you mentioned that you wanted to create that compact feeling of an occupation but it also reminded me of the human chain. Could you talk about the human chain a little bit?

MNE: Right! That was actually the original inspiration for that, that I totally forgot. So during the 1986 protest they began the occupation by forming this giant human chain around Eliot and I just – one, that must have taken so many bodies. I really don’t know how many people it would take to make a human chain around Eliot, but more than I think—well, a really significant amount of people. I wanted to bring in that chain movement, and that physical closeness of creating a space with your bodies. So, yeah, they literally had to make a chain by weaving in and out of everyone.

RC: And the last thing I wondered if you’d comment on was your choice to put the — to print the Quest articles and that be the way that you shared some of the information. Because at other stops some people had verbally talked about the history, but you chose to do it through print and that was a very conscious decision. I wondered if you’d talk a little bit about that.

MNE: Yeah, so I wanted to go over from the Black Student Union was and what the demands from the protestors or the organizers for the call for divestment were. But I felt like if I said them aloud it would feel weird because I wasn’t one of those organizers, I wasn’t an organizer of the past few occupations, like it didn’t feel like my place to use all of these “I” and “we” statements that were in them. So I wanted to provide that information to people without it verbally coming from my mouth. And so I printed them out.

Also the cookies were a reference to this cookie thing that happened last year when [then] President Kroger had promised to hold these “cookie” office hours but the joke was that he never attended his office hours.

RC: Was it true, did the [2017/18] protestors then hand out cookies?

MNE: Yeah we had a little cookie time. [laughter]

Stop #4: Library; Tom Kelly Affair (1947) – Choreographer, Hannah Jensvold

MM: One thing that was shocking to me – and I think it was shocking because I thought that I would have learned it in earlier projects that I’ve done while being at Reed—is the number of veterans on campus after World War II. And I guess it makes sense because the country was inundated suddenly with veterans because we had suddenly had a draft, and suddenly all these people were forcibly veterans. Thinking about having a strong even like past military presence on campus is so foreign to me. So foreign to me. And I’ve done one or two projects that have also been productions about military sentiment on Reed College campus, and so one thing that we had never talked about, I guess, during those times was post-World War II. And so thinking about students rallying around a veteran who was wrongfully arrested for not carrying around his discharge papers, or whatever—I just can’t even imagine that happening now. I imagine people posting on Facebook about how anyone in the military deserves—whatever, you know? So that was one thing that really struck me and has stuck with me.

HJ: I felt the same way and I think that was maybe was a part of why I chose that event to talk about because it is really hard to imagine today’s Reed community rallying around a veteran. And I think that maybe played into part of my choice of the poem too it felt like a very foreign context of having so many student veterans at Reed and in this time of a draft having happened, but also—and that’s all to say, it’s the one I was also kind of concerned that Reed community members would not take the story well, particularly Reed students would not take the story well, and be like, “Why are you perpetuating this history? Is this pro-military?” It was interesting because the values at the core of it had to do with this unfair treatment by police, which is obviously a huge issue today, and also mental health, because as I dug deeper into that story, a large part of it too was, Tom Kelly was in a program for rehabilitation after experiencing very extreme PTSD. And part of what happened—I eventually found an oral history from an alum who was there—was that he did not initially obey the officer because he was having some sort of moment of trauma reaction where he kind of was, like, struck still. And so that’s why the officer shoved him into the car and then came up with, “You’re not carrying your discharge papers” as a reason to arrest him.

EL: I think it was really interesting to me that we had specifically yours [Hannah] about Tom Kelly and yours [Alli] about 9/11—like, such extremely different reactions from Reedies as to larger issues in this country. Where, in that case [the Tom Kelly affair], they were supporting a veteran, and in the 9/11 case, they were trying to invert flags and I think you said they were burning flags? I don’t remember. No? Ok, never mind.

AF: Not this time.

HJ: I think that was the Trump election.

AF: Yeah, that was the Trump election.

EL: That did happen. Just how strongly different those sentiments towards America are. And I think it is very different with an instance of a Reedie being unfairly treated by police and a national crisis—those are obviously going to elicit different responses. But they’re just very different responses.

Stop #5: College Entrance; Building Services Employees Union Protests (1961) – Choreographer: Erin Lauderdale

RC: [Erin,] your site was one of the least literal in terms of the place where it happened. Talk about choice of location.

EL: The protest did happen, it just said “the entrance to the college” which is pretty vague. I thought about what represents the entrance the most? Going back into the archives I was looking for more information about what Reed looked like in the 60s, and that was the only entrance to the campus at the time, so that ended up working out perfectly. I assume the pickets did actually happen there. I think they have happened on Woodstock, on the street, but I didn’t want to lead a group of audience members onto the street.

RC: That makes me think about the format: tour not a protest. Not asking audience to embody and take up any of these causes. How do you make a dance that’s about protest but isn’t a protest? That is inspired by, somehow calls upon, using this tour format to look at history of protest was a good solution that you all came up with, logistically, also in terms of the intervention it’s making. We’re not going to go on the street and block traffic, this isn’t a protest but we’re honoring this history of it.

EL: I ended up feeling a little bit like we as performers were protest because we were chanting. But it was a picket so I felt like we had to in some way embody it.

HJ: What I thought was interesting too was that yours Erin was that the only the place we were at where the actual tour would have been visible to people on Woodstock who were not on campus and could have looked like a protest to people who were driving by. And I think, obviously, because it is at the entrance, that’s significant, even though all of the protests and moments of dissent that we talked about of course had ramifications and connect to things far outside of just Reed, yours felt like one of the ones, maybe bc it was the only one that really was thinking about the position of different people in the Reed community, not just students, it was building service workers protesting their treatment at Reed.

EL: I was really glad to find out their union is still in tact. When student workers’ union stuff was going on, I was like what about people who are not students? Good to know they do have a union.

Why Dance?

RC: So now I’m going to ask the “Why dance?” question [laughter], which is something along the lines of …We’ve talked a bit about these histories being preserved and perpetuated in different ways, right? In print media, social media, the narrative of prospie tours, this official image put forth of the school by administration, all these ways in which narrative of a place and histories of a place are shared. And what we presented to people definitely made use of all of the [media]: words, print, and all of those things. But also [it] was approached as well from a choreographic logic. Morgan explained how the logic of the procession was appropriate for experiencing that history, and I wonder if you could all reflect on how, either in your own decision-making process, or in experiencing other peoples’ part of the tour, how embodiment adds to the way that you chose to lift up these histories and give a spotlight these lesser-told histories.

HJ: I’m certainly thinking a lot about what Morgan said earlier before we started the recording, about that moment of embodiment in Eliot. And I don’t know if you want to rehash what you said there?

MM: So for that part of the performance, we were standing in a single-file line and from the beginning of the line one person wove through back and forth between the bodies, and then we all filed back through until the person that started was at the front of the line again. And during that moment of weaving through and getting in the way of people and preventing other people from moving, the intention of a sit-in, protest, which was most often the kind of protest most often utilized in Eliot, especially on the third floor, particularly at my time at Reed, disrupts people’s paths. It gets in people’s ways. And that was something I hadn’t really realized about that choreography that Maya made until I was doing it and then I realized, and I got it. Crazy!

[…]

EL: This kind of goes back to what you [Morgan] were saying earlier about why you chose to process through your sites, but I think that also applies to the whole tour generally. Walking through campus and being like, “Oh yeah, there have been other people here who have had very strong opinions that have led them to dissent. Like, in this space, that my body is currently [in]. I think that that also really fed into what we were trying to get the audience to think about.

AF: That just makes me think of how us placing our bodies in that site in remembrance of the protest that have happened is also a testament that, like, “You can also put your body here and protest. You are here now; you can be here for a reason. People have done it before you.”

HJ: And it just makes me think a lot about, that I think both in protests and in dance and in their overlap, that—and it’s something, I don’t know, maybe it’s not so specific to this and maybe it’s just kind of my “Why dance?” always—is that there’s something that can’t be captured in words that is that embodied knowledge of physically being in a place and physically doing something and the way that that can disrupt or enact that just words can’t do. I think that was a really amazing way to experience some of these histories about this place that we all are at right now.

Concluding Thoughts on Dancer Citizen Pedagogy

What is dancer citizen pedagogy? Writing about this project has given me an opportunity to articulate some responses to that question. My reflection is a riff on the definition of “dancer citizen” offered by the editors of this journal, as stated on the homepage:

This endeavor grows out of our belief in the role of the artist as public intellectual, our curiosity about how dancers observe, explain and comment on the world, and an understanding of the obligation we hold to seek and develop solutions for the challenges facing the communities in which we live and work. We recognize that our diverse roles, experiences, and perspectives as practitioners constitute a unique body of knowledge in the world.

First, dancer citizen pedagogy teaches students how to take up the role of the artist as public intellectual. Dancer citizen pedagogues shepherd students toward crafting dance experiences (performances, workshops, happenings, etc.) that engage with multiple publics to ask questions, unearth histories, issue critiques, build communities, and offer frameworks for understanding the world around them. Teachers guide students through the process of harnessing their own observations, curiosities, and critiques as springboards for artistic-intellectual inquiry. In creating “Same As It Ever Was,” this meant taking seriously students’ desire to hold their school accountable, and to guide them to the archive as a way to deepen their informed critiques. If that is the “intellectual” part, the “public” part is also to teach them about how to cultivate audiences, which includes but exceeds the question of filling seats. This might mean entering conversations and even collaborations across campus, in their communities, and online as a way to involve people who care about the same things they care about.

Dancers as public intellectuals fill a role different from journalists or historians. As such, dancer citizen pedagogy also empowers dancers to cultivate embodied performance and choreographic logic as powerful tools for explaining and commenting on the world—tools that are not inferior but rather complementary to other modes of engaged citizenship, such as voting and protesting. As reflected in the comments above, the students noticed several powerful impacts of the kinesthetic, choreographic aspect of their performance: it collapsed time between past and present political moments; stirred up the affective experience of blocking pathways during a sit-in; and invoked sustained histories of dissent by engaging in durational physical activity. One goal of dancer citizen pedagogy is to guide students through a scaffolded process in which they build upon deep research to create performances/experiences that connect audiences/participants with visceral, affective, and poetic points of entry to challenging topics.

Finally, dancer citizen pedagogy shows students ways to extend their engagement beyond the creative process, to “develop solutions for the challenges facing the communities in which we live and work.” While I did not ask my Reed students to take this step, I am considering several ways in which the course and/or project could be deepened and expanded in future versions. For example, we did not discuss approaching Reed’s campus tour organizers to see if they would be interested in adopting our alternative campus tour to their prospie tour scripts. It’s entirely possible that there might have been interest in doing so. Had the project been the focus of the entire semester, we could have imagined numerous avenues for activism and engagement that spawned from our performance creation.

Another area for future improvement involves the quality of the performance itself. Given the time constraints of the course (and the definitive performance date chosen by Reed Arts Week organizers), we lacked substantial time to rehearse. In fact, the first and only time that we ran the entire piece was during its singular performance! While students and I were moved and inspired by the process, the performance itself would have benefitted from much more time to prepare. Walking backward while speaking extemporaneously, projecting one’s voice out of doors, working a portable microphone, organizing bodies into a single file line —all of these actions require some training and practice. We were acutely reminded of Susan Foster’s point that, no matter how seemingly colloquial or spontaneous, dance performances and protests are the result of training and rehearsal (“Choreographies of Protest,” 410).

Time is not the only constraint on dancer citizen pedagogy. Engaging in such teaching may not be possible for every educator due to different levels of contingency and precarity. Opting for syllabus topics that skirt controversial and/or political topics altogether can be an understandable recourse for faculty members who may face real consequences for rocking the boat.

Even if the will is there, it takes time and energy to develop meaningful partnerships with on- and off-campus organizations. Two examples, culled from a mentor and colleague, come to mind. First is Janice Ross’s “Dance In Prisons” course at Stanford University, which she has been teaching for nearly two decades, and in which I had the opportunity to participate during a postdoctoral fellowship at Stanford. Team-taught with a juvenile justice lawyer, Ross brings undergraduates to juvenile detention centers to join dance workshops with youth inside. Second is Victoria Fortuna’s “Community Dance and Collective Creation” course at Reed College. (Fortuna is an Assistant Professor in the Reed Dance Department, and in fact, I was a Visiting Assistant Professor there during her sabbatical leave.) Fortuna often partners with a nonprofit organization, such as Don’t Shoot Portland, bringing members of the Reed community together with Portland residents to make a performance piece about a shared topic of interest or concern. These kinds of partnerships are not always plausible if instructors are moving through institutions in temporary and/or part-time positions. On the other hand, contingent positions can be a source of power; my status as a one-year visitor may have made it less risky for me to support students’ dissent against the College. In whatever ways we face discouragement, it is worthwhile for dancer citizens to craft our classrooms into zones of rehearsal for engaged citizenship, approaching this as something that higher education (students, faculty, administration) needs—and might even want.

My hope is that these five young choreographers, two of whom have since graduated from Reed College, will see this experience as one zone of training that motivates their future endeavors as artists, organizers, and citizens. We are all, in our divergent roles and respective communities, dancer citizens, and creating “Same As It Ever Was” was an opportunity for us to train our bodies, minds, and spirits for choreographing dissent.

1. Susan Foster, "Choreographies of Protest," Theatre Journal 55.3 (2003): 395-412; Danielle Goldman, “Bodies on the Line: Contact Improvisation and Techniques of Nonviolent Protest,” in I Want to Be Ready: Improvised Dance as a Practice of Freedom (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), pp. 94-111; Anusha Kedhar, “Hands up! Don’t Shoot! Gesture, Choreography, and Protest in Ferguson,” The Feminist Wire, October 6, 2014 http://www.thefeministwire.com/2014/10/protest-in-ferguson/; Gregory King and Ellen Chenoweth, “When Dance Voices Protest,” Conversations Across the Field of Dance Studies Vol. 36 (2016), pp. 55-63. back to text

2. Student Erin Lauderdale presented to the class research on WERK for Peace, a group of queer activists best known for their dance party protest outside of Mike Pence’s house days before President Trump’s inauguration. See also Natalie Zervou and Meghan Quinlan’s conversation in Issue 4 of The Dancer-Citizen. back to text

3. For those who notice a reference to the rock band The Talking Heads—it is intentional. “Same as it ever was” is a prominent lyric in a song, “Once In a Lifetime,” from the album, Stop Making Sense. That album provides the soundtrack to two social dances that open and close each school year. back to text

4. Meister found much of her information in issues of the student newspaper, Reed College Quest, printed throughout the 1970s. These include many editorials regarding sexism on Reed’s campus, such as the lack of women in the Humanities 110 curriculum and limited gynecological services available to students; notices of the “Wimmin’s Center /Feminist Union” and rape awareness group meetings; and business regarding the establishment of the Women’s Center. For example, page 4 of Vol. 71, No. 15 (Feb. 9, 1979) displays all student organizations receiving funding from student body fees, among them “Women’s Center/Fem.” back to text

5. Sample citations from Fatone’s research into archived editions of Reed College Quest, Reed’s student newspaper, include: Eleanor B., “American Flag Turned Upside-Down in Front of Eliot in Unpatriotic Prank,” Vol. 183, No. 5 (Sept. 25, 2001); “Senate Beat: The American Flag Controversy,” Vol. 183, No. 5 (Sept. 25, 2001); Michael O’Brien, “Director of Community Safety Responds to the Flag Controversy,” Vol. 183, No. 6 (Oct. 2, 2001); Andrew R., “Turning the Flag Upside Down Shows a Lack of Respect, Denies Innocence of Victims,” Vol. 183, No. 8 (Oct. 23, 2001); Eric N., “Why I Don’t Hate Osama Bin Laden: Thoughts on Fundamentalism,” Vol. 183, No. 8 (Oct. 23, 2001). back to text

6. Nájera Evans learned much of this history from student newspaper sources, especially Reed College Quest Vol. 86, No. 16 (Jan. 27, 1986) and the Special BSU Edition of Reed College Quest (Oct. 15, 1968). back to text

7. Tom Kelly was a World War II veteran came to Reed College through a veteran rehabilitation program, having experienced extreme PTSD after being discharged. On February 6, 1947, Kelly was reading a book of poetry while he sat on the curb outside the Reed College library after a late night of studying. A Portland police officer patrolling near campus - a common practice at the time due to fear of communist Reed students - yelled for Kelly to come over the patrol car. Kelly was struck motionless with panic, a reaction related to his PTSD, and the officer proceeded to arrest him for failing to carry his military discharge papers, shoving him into the back of the patrol car. He was detained by Portland police into the next day. The next night, Reed students gathered in the same spot outside the library where, under the moonlight, they read poetry by Percy Shelley and protested the unfair detainment of their classmate. The story received media coverage throughout the nation, and the Portland police’s mistreatment of Kelly captured the attention of the ACLU, who took legal action on his behalf. Jensvold constructed this account of the Kelly by compiling information from independent news sources and oral history projects for institutional memory at Reed College. Sources include “The New (Olde) Reed Almanac,” Reed Magazine Vol. 90, No. 4 (Dec. 2011); “Education: Shelley by Moonlight,” Time Magazine Feb. 17, 1947; “An Oral History of Reed College,” Reed Magazine (Feb. 2004); “Shelley by Moonlight,” TIME Magazine Vol. 49, Issue 7 (Feb. 17, 1947). back to text

8. “Labor Dispute Settled, College Makes Concession to Union,” Reed College Quest Vol. 51, no. 1 (Sept. 18, 1961). back to text

9. Maya Nájera Evans was absent from class that day, but agreed to have a recorded dialogue with me as part of another class of mine in which they were enrolled that semester. Therefore, their reflections were addressed to a group of undergraduates who had not participated in the performance. back to text